|

Topics

Introduction

Problems Freedom Knowledge Mind Life Chance Quantum Entanglement Scandals Philosophers Mortimer Adler Rogers Albritton Alexander of Aphrodisias Samuel Alexander William Alston Anaximander G.E.M.Anscombe Anselm Louise Antony Thomas Aquinas Aristotle David Armstrong Harald Atmanspacher Robert Audi Augustine J.L.Austin A.J.Ayer Alexander Bain Mark Balaguer Jeffrey Barrett William Barrett William Belsham Henri Bergson George Berkeley Isaiah Berlin Richard J. Bernstein Bernard Berofsky Robert Bishop Max Black Susan Blackmore Susanne Bobzien Emil du Bois-Reymond Hilary Bok Laurence BonJour George Boole Émile Boutroux Daniel Boyd F.H.Bradley C.D.Broad Michael Burke Jeremy Butterfield Lawrence Cahoone C.A.Campbell Joseph Keim Campbell Rudolf Carnap Carneades Nancy Cartwright Gregg Caruso Ernst Cassirer David Chalmers Roderick Chisholm Chrysippus Cicero Tom Clark Randolph Clarke Samuel Clarke Anthony Collins August Compte Antonella Corradini Diodorus Cronus Jonathan Dancy Donald Davidson Mario De Caro Democritus William Dembski Brendan Dempsey Daniel Dennett Jacques Derrida René Descartes Richard Double Fred Dretske Curt Ducasse John Earman Laura Waddell Ekstrom Epictetus Epicurus Austin Farrer Herbert Feigl Arthur Fine John Martin Fischer Frederic Fitch Owen Flanagan Luciano Floridi Philippa Foot Alfred Fouilleé Harry Frankfurt Richard L. Franklin Bas van Fraassen Michael Frede Gottlob Frege Peter Geach Edmund Gettier Carl Ginet Alvin Goldman Gorgias Nicholas St. John Green Niels Henrik Gregersen H.Paul Grice Ian Hacking Ishtiyaque Haji Stuart Hampshire W.F.R.Hardie Sam Harris William Hasker R.M.Hare Georg W.F. Hegel Martin Heidegger Heraclitus R.E.Hobart Thomas Hobbes David Hodgson Shadsworth Hodgson Baron d'Holbach Ted Honderich Pamela Huby David Hume Ferenc Huoranszki Frank Jackson William James Lord Kames Robert Kane Immanuel Kant Tomis Kapitan Walter Kaufmann Jaegwon Kim William King Hilary Kornblith Christine Korsgaard Saul Kripke Thomas Kuhn Andrea Lavazza James Ladyman Christoph Lehner Keith Lehrer Gottfried Leibniz Jules Lequyer Leucippus Michael Levin Joseph Levine George Henry Lewes C.I.Lewis David Lewis Peter Lipton C. Lloyd Morgan John Locke Michael Lockwood Arthur O. Lovejoy E. Jonathan Lowe John R. Lucas Lucretius Alasdair MacIntyre Ruth Barcan Marcus Tim Maudlin James Martineau Nicholas Maxwell Storrs McCall Hugh McCann Colin McGinn Michael McKenna Brian McLaughlin John McTaggart Paul E. Meehl Uwe Meixner Alfred Mele Trenton Merricks John Stuart Mill Dickinson Miller G.E.Moore Ernest Nagel Thomas Nagel Otto Neurath Friedrich Nietzsche John Norton P.H.Nowell-Smith Robert Nozick William of Ockham Timothy O'Connor Parmenides David F. Pears Charles Sanders Peirce Derk Pereboom Steven Pinker U.T.Place Plato Karl Popper Porphyry Huw Price H.A.Prichard Protagoras Hilary Putnam Willard van Orman Quine Frank Ramsey Ayn Rand Michael Rea Thomas Reid Charles Renouvier Nicholas Rescher C.W.Rietdijk Richard Rorty Josiah Royce Bertrand Russell Paul Russell Gilbert Ryle Jean-Paul Sartre Kenneth Sayre T.M.Scanlon Moritz Schlick John Duns Scotus Albert Schweitzer Arthur Schopenhauer John Searle Wilfrid Sellars David Shiang Alan Sidelle Ted Sider Henry Sidgwick Walter Sinnott-Armstrong Peter Slezak J.J.C.Smart Saul Smilansky Michael Smith Baruch Spinoza L. Susan Stebbing Isabelle Stengers George F. Stout Galen Strawson Peter Strawson Eleonore Stump Francisco Suárez Richard Taylor Kevin Timpe Mark Twain Peter Unger Peter van Inwagen Manuel Vargas John Venn Kadri Vihvelin Voltaire G.H. von Wright David Foster Wallace R. Jay Wallace W.G.Ward Ted Warfield Roy Weatherford C.F. von Weizsäcker William Whewell Alfred North Whitehead David Widerker David Wiggins Bernard Williams Timothy Williamson Ludwig Wittgenstein Susan Wolf Xenophon Scientists David Albert Philip W. Anderson Michael Arbib Bobby Azarian Walter Baade Bernard Baars Jeffrey Bada Leslie Ballentine Marcello Barbieri Jacob Barandes Julian Barbour Horace Barlow Gregory Bateson Jakob Bekenstein John S. Bell Mara Beller Charles Bennett Ludwig von Bertalanffy Susan Blackmore Margaret Boden David Bohm Niels Bohr Ludwig Boltzmann John Tyler Bonner Emile Borel Max Born Satyendra Nath Bose Walther Bothe Jean Bricmont Hans Briegel Leon Brillouin Daniel Brooks Stephen Brush Henry Thomas Buckle S. H. Burbury Melvin Calvin William Calvin Donald Campbell John O. Campbell Sadi Carnot Sean B. Carroll Anthony Cashmore Eric Chaisson Gregory Chaitin Jean-Pierre Changeux Rudolf Clausius Arthur Holly Compton John Conway Simon Conway-Morris Peter Corning George Cowan Jerry Coyne John Cramer Francis Crick E. P. Culverwell Antonio Damasio Olivier Darrigol Charles Darwin Paul Davies Richard Dawkins Terrence Deacon Lüder Deecke Richard Dedekind Louis de Broglie Stanislas Dehaene Max Delbrück Abraham de Moivre David Depew Bernard d'Espagnat Paul Dirac Theodosius Dobzhansky Hans Driesch John Dupré John Eccles Arthur Stanley Eddington Gerald Edelman Paul Ehrenfest Manfred Eigen Albert Einstein George F. R. Ellis Walter Elsasser Hugh Everett, III Franz Exner Richard Feynman R. A. Fisher David Foster Joseph Fourier George Fox Philipp Frank Steven Frautschi Edward Fredkin Augustin-Jean Fresnel Karl Friston Benjamin Gal-Or Howard Gardner Lila Gatlin Michael Gazzaniga Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen GianCarlo Ghirardi J. Willard Gibbs James J. Gibson Nicolas Gisin Paul Glimcher Thomas Gold A. O. Gomes Brian Goodwin Julian Gough Joshua Greene Dirk ter Haar Jacques Hadamard Mark Hadley Ernst Haeckel Patrick Haggard J. B. S. Haldane Stuart Hameroff Augustin Hamon Sam Harris Ralph Hartley Hyman Hartman Jeff Hawkins John-Dylan Haynes Donald Hebb Martin Heisenberg Werner Heisenberg Hermann von Helmholtz Grete Hermann John Herschel Francis Heylighen Basil Hiley Art Hobson Jesper Hoffmeyer John Holland Don Howard John H. Jackson Ray Jackendoff Roman Jakobson E. T. Jaynes William Stanley Jevons Pascual Jordan Eric Kandel Ruth E. Kastner Stuart Kauffman Martin J. Klein William R. Klemm Christof Koch Simon Kochen Hans Kornhuber Stephen Kosslyn Daniel Koshland Ladislav Kovàč Leopold Kronecker Bernd-Olaf Küppers Rolf Landauer Alfred Landé Pierre-Simon Laplace Karl Lashley David Layzer Joseph LeDoux Gerald Lettvin Michael Levin Gilbert Lewis Benjamin Libet David Lindley Seth Lloyd Werner Loewenstein Hendrik Lorentz Josef Loschmidt Alfred Lotka Ernst Mach Donald MacKay Henry Margenau Lynn Margulis Owen Maroney David Marr Humberto Maturana James Clerk Maxwell John Maynard Smith Ernst Mayr John McCarthy Barbara McClintock Warren McCulloch N. David Mermin George Miller Stanley Miller Ulrich Mohrhoff Jacques Monod Vernon Mountcastle Gerd B. Müller Emmy Noether Denis Noble Donald Norman Travis Norsen Howard T. Odum Alexander Oparin Abraham Pais Howard Pattee Wolfgang Pauli Massimo Pauri Wilder Penfield Roger Penrose Massimo Pigliucci Steven Pinker Colin Pittendrigh Walter Pitts Max Planck Susan Pockett Henri Poincaré Michael Polanyi Daniel Pollen Ilya Prigogine Hans Primas Giulio Prisco Zenon Pylyshyn Henry Quastler Adolphe Quételet Pasco Rakic Nicolas Rashevsky Lord Rayleigh Frederick Reif Jürgen Renn Giacomo Rizzolati A.A. Roback Emil Roduner Juan Roederer Robert Rosen Frank Rosenblatt Jerome Rothstein David Ruelle David Rumelhart Michael Ruse Stanley Salthe Robert Sapolsky Tilman Sauer Ferdinand de Saussure Jürgen Schmidhuber Erwin Schrödinger Aaron Schurger Sebastian Seung Thomas Sebeok Franco Selleri Claude Shannon James A. Shapiro Charles Sherrington Abner Shimony Herbert Simon Dean Keith Simonton Edmund Sinnott B. F. Skinner Lee Smolin Ray Solomonoff Herbert Spencer Roger Sperry John Stachel Kenneth Stanley Henry Stapp Ian Stewart Tom Stonier Antoine Suarez Leonard Susskind Leo Szilard Max Tegmark Teilhard de Chardin Libb Thims William Thomson (Kelvin) Richard Tolman Giulio Tononi Peter Tse Alan Turing Robert Ulanowicz C. S. Unnikrishnan Nico van Kampen Francisco Varela Vlatko Vedral Vladimir Vernadsky Clément Vidal Mikhail Volkenstein Heinz von Foerster Richard von Mises John von Neumann Jakob von Uexküll C. H. Waddington Sara Imari Walker James D. Watson John B. Watson Daniel Wegner Steven Weinberg August Weismann Paul A. Weiss Herman Weyl John Wheeler Jeffrey Wicken Wilhelm Wien Norbert Wiener Eugene Wigner E. O. Wiley E. O. Wilson Günther Witzany Carl Woese Stephen Wolfram H. Dieter Zeh Semir Zeki Ernst Zermelo Wojciech Zurek Konrad Zuse Fritz Zwicky Presentations ABCD Harvard (ppt) Biosemiotics Free Will Mental Causation James Symposium CCS25 Talk Evo Devo September 12 Evo Devo October 2 Evo Devo Goodness Evo Devo Davies Nov12 |

About the Information Philosopher

Information Philosophy (I-Phi) is a new philosophical method grounded in science, especially modern physics, biology, psychology, neuroscience, and the science of information. Information philosophy offers novel solutions to classical problems in philosophy, notably freedom of the will, the objective foundation of values, and the problem of knowledge (epistemology). Insights into human freedom and cosmic values could form the basis for a new system of belief and a guide to moral conduct.

Information analysis also provides insight into several problems in modern physics, including an information interpretation of quantum mechanics and the quantum mechanical irreversibility that drives the second law of thermodynamics. Perhaps most importantly, information creation explains how life, mind, purpose, and consciousness entered the material universe.

Bob Doyle calls himself the Information Philosopher. He has possibly read more works of philosophers and scientists than any other modern thinker, and has critically analyzed and written about the key ideas of hundreds of them on these I-Phi web pages, as seen in the left navigation.

Bob is now an Associate in the Harvard Astronomy Department. He and his wife Holly, earned Ph.D's in Astrophysics from Harvard University in 1968. Anti-nepotism rules prevented them from getting academic positions in the same university (long since eliminated by the rise of feminism). Bob decided to become an entrepreneur in the hopes of earning an independent income so he and Holly could remain in Cambridge near Harvard. There Bob could pursue his lifelong interest in some great problems in philosophy, using the resources of Harvard's excellent libraries.

Bob's Ph.D. thesis The Continuous Spectrum of the Hydrogen Quasi-Molecule was on the quantum mechanics of two hydrogen atoms colliding. He called them a hydrogen "quasi-molecule (two hydrogen atoms absorbing and emitting light while they are colliding and separating). It is the interaction of matter with radiation that makes atomic collisions ontologically indeterministic and irreversible, as was first seen by Albert Einstein in 1916. Chance and microscopic irreversibility are needed to understand the creation of all information structures, in spite of the second law of thermodynamics which destroys order and information.

Bob's thesis provided him a strong insight into the problem of the entanglement of two particles that had once been parts of a two-particle system like his hydrogen "quasi-molecule."

In May 1935 Einstein and two colleagues published their paper known as the EPR Paradox. They described colliding atoms as continuing to act on one another however far apart they become "separated." Einstein later called this "spooky action at a distance." But just months later, in September 1935, Erwin Schrödinger, the inventor of wave mechanics and the quantum wave function Ψ, told Einstein that the atoms had become "entangled" and are best described with a two-particle wave function Ψ12 that cannot be separated into the product of two independent single-particle wave functions Ψ1 and Ψ2 as long as they are undisturbed.

Following Schrödinger's wave mechanics, Bob Doyle's quasi-molecular wave function cannot be separated into the product of two independent atomic wave functions. The quasi-molecule keeps the atomic properties perfectly correlated however far apart the atoms are found to be separated when measured, not because there are active connections between the atoms, but because the spherical symmetry of the molecular wave function conserves fundamental shared properties of the atoms like total energy, linear momentum, angular momentum, and spin.

Conservation laws are deeply fundamental to both classical mechanics and quantum mechanics. David Bohm's 1952 version of Einstein's 1935 EPR paradox is based on a hydrogen molecule that separates into two atoms. Bohm does not mention that Schrödinger had said the atoms cannot be separated until a decohering and disentangling measurement is made. Bohm does note that their electron spins are always measured to be in opposite directions, summing to spin zero. But Bohm does not mention that this conserves the total spin angular momentum zero of the molecule's spherically symmetric singlet state. Bob suggested that this conserved spin zero could be described as a "hidden constant of the motion." There is no need for any "hidden variables" traveling with the atoms that Einstein, Bohm, and later John Bell, thought could explain the perfect correlations of atomic properties when "separating" atoms are measured.

Bob submitted his thesis in 1965, but flunked his oral exam, probably because he had taught himself atomic and molecular quantum mechanics and was not fluent enough at the blackboard with the formal mathematics. His examiners required him to take graduate courses in quantum mechanics in the Harvard physics department, and get his thesis accepted for publication, before granting his Ph.D.

It was a stressful time, without his degree. Bob was offered teaching positions at Boston University and Brandeis University. He accepted the Brandeis job and supplemented his income as a science consultant to Boston-area high schools. Ten schools west of Boston formed the TEC Cooperative and asked Bob to write a proposal to fund a planetarium. Bob's proposal won a $150,000 grant to install a Spitz A3P projector at Natick High School in 1966.

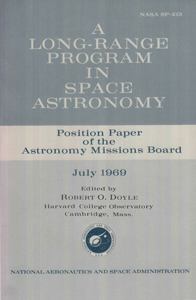

From 1967 to 1969 Bob was a scientific assistant to NASA's Astronomy Missions Board, who were charged with preparing A Long-Range Program in Space Astronomy. He was appointed by Leo Goldberg, who was the chairman of the Harvard Department of Astronomy, the director of the Harvard College Observatory, the president of the American Astronomical Society, and past president of the International Astronomical Union, the head of every scientific society that Bob belonged to!

Bob met with the Astronomy Missions Board every month, and met with its seven sub-discipline panels multiple times each year. NASA demanded that in addition to proposing new missions for space satellites, rockets, and balloons in the various fields, that the board also "assign funding priorities" to the various fields. Board members were adamantly opposed. As scientists, they should not tell NASA how much money to spend on solar versus stellar versus planetary astronomy, for example.

After many meetings in which the AMB refused to assign priorities as the NASA staff was insisting, Leo Goldberg offered to resign and dissolve the board unless it could address mission costs and budgets for the different sub-disciplines. The sub-discipline panels had prepared reports on their minimum, middle, and most ambitious programs and had provided cost estimates for each, but they could not provide guidance as to which field was most likely to provide the most important new space astronomical research.

At their next meeting, at Kitt Peak Observatory in Arizona, with Leo Goldberg's threat to resign in mind, Bob Doyle added up the total costs for minimum balanced, medium, and most ambitious space astronomy missions as approximtely $250 million, $500 million, and $1 billion per year. At that time the space astronomy program was costing $180 million a year. NASA associate administrator Homer Newell attended this meeting. He was pleased with the funding priorities and said that if the position paper of the board was edited, he would authorize the government printing office to publish it and submit it to Congress with a request for "new starts" in space astronomy (the first since John F. Kennedy's presidency).

Bob Doyle calls himself the Information Philosopher. He has possibly read more works of philosophers and scientists than any other modern thinker, and has critically analyzed and written about the key ideas of hundreds of them on these I-Phi web pages, as seen in the left navigation.

Bob is now an Associate in the Harvard Astronomy Department. He and his wife Holly, earned Ph.D's in Astrophysics from Harvard University in 1968. Anti-nepotism rules prevented them from getting academic positions in the same university (long since eliminated by the rise of feminism). Bob decided to become an entrepreneur in the hopes of earning an independent income so he and Holly could remain in Cambridge near Harvard. There Bob could pursue his lifelong interest in some great problems in philosophy, using the resources of Harvard's excellent libraries.

Bob's Ph.D. thesis The Continuous Spectrum of the Hydrogen Quasi-Molecule was on the quantum mechanics of two hydrogen atoms colliding. He called them a hydrogen "quasi-molecule (two hydrogen atoms absorbing and emitting light while they are colliding and separating). It is the interaction of matter with radiation that makes atomic collisions ontologically indeterministic and irreversible, as was first seen by Albert Einstein in 1916. Chance and microscopic irreversibility are needed to understand the creation of all information structures, in spite of the second law of thermodynamics which destroys order and information.

Bob's thesis provided him a strong insight into the problem of the entanglement of two particles that had once been parts of a two-particle system like his hydrogen "quasi-molecule."

In May 1935 Einstein and two colleagues published their paper known as the EPR Paradox. They described colliding atoms as continuing to act on one another however far apart they become "separated." Einstein later called this "spooky action at a distance." But just months later, in September 1935, Erwin Schrödinger, the inventor of wave mechanics and the quantum wave function Ψ, told Einstein that the atoms had become "entangled" and are best described with a two-particle wave function Ψ12 that cannot be separated into the product of two independent single-particle wave functions Ψ1 and Ψ2 as long as they are undisturbed.

Following Schrödinger's wave mechanics, Bob Doyle's quasi-molecular wave function cannot be separated into the product of two independent atomic wave functions. The quasi-molecule keeps the atomic properties perfectly correlated however far apart the atoms are found to be separated when measured, not because there are active connections between the atoms, but because the spherical symmetry of the molecular wave function conserves fundamental shared properties of the atoms like total energy, linear momentum, angular momentum, and spin.

Conservation laws are deeply fundamental to both classical mechanics and quantum mechanics. David Bohm's 1952 version of Einstein's 1935 EPR paradox is based on a hydrogen molecule that separates into two atoms. Bohm does not mention that Schrödinger had said the atoms cannot be separated until a decohering and disentangling measurement is made. Bohm does note that their electron spins are always measured to be in opposite directions, summing to spin zero. But Bohm does not mention that this conserves the total spin angular momentum zero of the molecule's spherically symmetric singlet state. Bob suggested that this conserved spin zero could be described as a "hidden constant of the motion." There is no need for any "hidden variables" traveling with the atoms that Einstein, Bohm, and later John Bell, thought could explain the perfect correlations of atomic properties when "separating" atoms are measured.

Bob submitted his thesis in 1965, but flunked his oral exam, probably because he had taught himself atomic and molecular quantum mechanics and was not fluent enough at the blackboard with the formal mathematics. His examiners required him to take graduate courses in quantum mechanics in the Harvard physics department, and get his thesis accepted for publication, before granting his Ph.D.

It was a stressful time, without his degree. Bob was offered teaching positions at Boston University and Brandeis University. He accepted the Brandeis job and supplemented his income as a science consultant to Boston-area high schools. Ten schools west of Boston formed the TEC Cooperative and asked Bob to write a proposal to fund a planetarium. Bob's proposal won a $150,000 grant to install a Spitz A3P projector at Natick High School in 1966.

From 1967 to 1969 Bob was a scientific assistant to NASA's Astronomy Missions Board, who were charged with preparing A Long-Range Program in Space Astronomy. He was appointed by Leo Goldberg, who was the chairman of the Harvard Department of Astronomy, the director of the Harvard College Observatory, the president of the American Astronomical Society, and past president of the International Astronomical Union, the head of every scientific society that Bob belonged to!

Bob met with the Astronomy Missions Board every month, and met with its seven sub-discipline panels multiple times each year. NASA demanded that in addition to proposing new missions for space satellites, rockets, and balloons in the various fields, that the board also "assign funding priorities" to the various fields. Board members were adamantly opposed. As scientists, they should not tell NASA how much money to spend on solar versus stellar versus planetary astronomy, for example.

After many meetings in which the AMB refused to assign priorities as the NASA staff was insisting, Leo Goldberg offered to resign and dissolve the board unless it could address mission costs and budgets for the different sub-disciplines. The sub-discipline panels had prepared reports on their minimum, middle, and most ambitious programs and had provided cost estimates for each, but they could not provide guidance as to which field was most likely to provide the most important new space astronomical research.

At their next meeting, at Kitt Peak Observatory in Arizona, with Leo Goldberg's threat to resign in mind, Bob Doyle added up the total costs for minimum balanced, medium, and most ambitious space astronomy missions as approximtely $250 million, $500 million, and $1 billion per year. At that time the space astronomy program was costing $180 million a year. NASA associate administrator Homer Newell attended this meeting. He was pleased with the funding priorities and said that if the position paper of the board was edited, he would authorize the government printing office to publish it and submit it to Congress with a request for "new starts" in space astronomy (the first since John F. Kennedy's presidency).

Bob edited A Long-Range Program in Space Astronomy, which NASA submitted to Congress, leading to the launch of the High Energy Astronomical Observatory HEAO-1 satellites and subsequently the Einstein (HEAO-2) and Chandra observatory-class X-Ray missions, as well as a Large Space Telescope (LST), know=n affectionately as the Lyman Spitzer Telescope after the chairman of the AMB's optical astronomy panel. When launched in 1990, the LST became the Hubble telescope.

Bob sent a packet of collaboration materials to the Purple Mountain Observatory in Peking to enable them to make synchronous ground-based observations, and possibly obtain NASA x-ray data someday. This caused some controversy between the AMB and the NASA administration, since President Nixon's 1972 visit to open diplomatic relations with China was then still a year away.

When Congress approved the new mission starts proposed in the Long-Range Program, the space astronomy budget went up by many millions of dollars, hundreds of millions over the next two decades. A Collaborative Observing Program for SkyLab alone had a million dollar budget. Bob wondered about the amount of productive work needed to produce so many millions of dollars. And he wondered if he could create enough wealth to provide an independent income so he and Holly could stay in Cambridge.

At the last meeting of the Astronomy Missions Board, held at NASA Headquarters in Washington, it was just one month after the July 20, 1969 landing of men on the moon, and one month since the publication of The Long Range Program in Space Astronomy. Bob had lunch at the Mayflower Hotel with AMB members Bernie Burke of MIT, Arthur Code of U. Wisconsin, and George Field, of UC Berkeley. The $5 cost of a cheeseburger shocked them. It was the beginning of the 1970's inflation crisis, but Bob reminded them that they had just endorsed the spending of hundreds of millions of dollars! Did they appreciate how hard it is to create such wealth?

In 1970 Bob and Holly were visiting professors at the University of Washington. Holly taught a course in elementary astronomy and Bob a course on recent developments in space astronomy, based on his published Long Range Program.

Bob edited A Long-Range Program in Space Astronomy, which NASA submitted to Congress, leading to the launch of the High Energy Astronomical Observatory HEAO-1 satellites and subsequently the Einstein (HEAO-2) and Chandra observatory-class X-Ray missions, as well as a Large Space Telescope (LST), know=n affectionately as the Lyman Spitzer Telescope after the chairman of the AMB's optical astronomy panel. When launched in 1990, the LST became the Hubble telescope.

Bob sent a packet of collaboration materials to the Purple Mountain Observatory in Peking to enable them to make synchronous ground-based observations, and possibly obtain NASA x-ray data someday. This caused some controversy between the AMB and the NASA administration, since President Nixon's 1972 visit to open diplomatic relations with China was then still a year away.

When Congress approved the new mission starts proposed in the Long-Range Program, the space astronomy budget went up by many millions of dollars, hundreds of millions over the next two decades. A Collaborative Observing Program for SkyLab alone had a million dollar budget. Bob wondered about the amount of productive work needed to produce so many millions of dollars. And he wondered if he could create enough wealth to provide an independent income so he and Holly could stay in Cambridge.

At the last meeting of the Astronomy Missions Board, held at NASA Headquarters in Washington, it was just one month after the July 20, 1969 landing of men on the moon, and one month since the publication of The Long Range Program in Space Astronomy. Bob had lunch at the Mayflower Hotel with AMB members Bernie Burke of MIT, Arthur Code of U. Wisconsin, and George Field, of UC Berkeley. The $5 cost of a cheeseburger shocked them. It was the beginning of the 1970's inflation crisis, but Bob reminded them that they had just endorsed the spending of hundreds of millions of dollars! Did they appreciate how hard it is to create such wealth?

In 1970 Bob and Holly were visiting professors at the University of Washington. Holly taught a course in elementary astronomy and Bob a course on recent developments in space astronomy, based on his published Long Range Program.

At a departmental meeting, the chairman George Wallerstein told Bob that the University had recently built a telescope dome, but still lacked the funds for a telescope! Wallerstein and professor Paul Hodge asked if Bob might help them prepare a proposal to the National Science Foundation. Bob knew that Hodge had done pioneering work on the capture of extraterrestrial dust particles, using detectors on high altitude flights of the secret U-2 and SR71 planes. Hodge was working with atmospheric chemistry professor Robert Charlson, whose nephelometer was the state-of-the-art tool for studying clouds.

Bob's knew that science funding priorities in Washington looked very favorably on inter-disciplinary research. He suggested to Hodge and Charlson that they propose a project on astronomical techniques for research on the atmosphere he dubbed Project ASTRA, designing a report cover with an opening for the title. During a long sleepless night, Bob wrote up the core rationale for a $25,000 grant. Not only was the grant funded, but it won the NSF director's award for the most original grant that year, so funds did not come out of the NSF astronomy section budget, but from the director's own funds.

At a departmental meeting, the chairman George Wallerstein told Bob that the University had recently built a telescope dome, but still lacked the funds for a telescope! Wallerstein and professor Paul Hodge asked if Bob might help them prepare a proposal to the National Science Foundation. Bob knew that Hodge had done pioneering work on the capture of extraterrestrial dust particles, using detectors on high altitude flights of the secret U-2 and SR71 planes. Hodge was working with atmospheric chemistry professor Robert Charlson, whose nephelometer was the state-of-the-art tool for studying clouds.

Bob's knew that science funding priorities in Washington looked very favorably on inter-disciplinary research. He suggested to Hodge and Charlson that they propose a project on astronomical techniques for research on the atmosphere he dubbed Project ASTRA, designing a report cover with an opening for the title. During a long sleepless night, Bob wrote up the core rationale for a $25,000 grant. Not only was the grant funded, but it won the NSF director's award for the most original grant that year, so funds did not come out of the NSF astronomy section budget, but from the director's own funds.

From the Johnson Spacecraft Center in Houston, Bob coordinated the Collaborative Observing Program with the Skylab astronauts from 1973 to 1974, which allowed 250 astronomical observatories around the world to synchronize their white-light ground-based solar observations with X-Ray images made by the Skylab astronauts using the Apollo Telescope Mount on board Skylab.

In 1973 an undergraduate student in a Harvard astronomy class, A. Robert Cole, '74, asked if he could produce a film as a substitute for writing a term paper. He and Bob Doyle learned of new synchronous sound Super8 movie systems being developed, like Bell and Howell Filmosound and the documentary filmmaker Richard Leacock's "double-system" sync sound project, funded by a $300,000 grant from Polaroid founder Edwin Land to Leacock's MIT department of Architecture and Film.

Bob applied to Harvard president Derek Bok for a $7500 grant to acquire an MIT/Leacock system for North House, where Cole was a student and Doyle a faculty associate. President Bok refused the grant, saying that every Harvard house would be wanting the same amount of money. While a momentary setback, it proved a long-term benefit, because it motivated Bob to develop some new technology and a business based on it.

Working with his brother in law, Wendl Thomis, a systems analyst and programmer at IBM, and with NASA physicist and neighbor Jordan "Jay" Kirsch, Bob Doyle modified a low-cost Sony TC800B tape recorder owned by Bob Cole to synchronize Super8 magnetic film with a Super8 camera. U.S. patent 3,900,251 was awarded for the Super8 Sound Recorder.

From the Johnson Spacecraft Center in Houston, Bob coordinated the Collaborative Observing Program with the Skylab astronauts from 1973 to 1974, which allowed 250 astronomical observatories around the world to synchronize their white-light ground-based solar observations with X-Ray images made by the Skylab astronauts using the Apollo Telescope Mount on board Skylab.

In 1973 an undergraduate student in a Harvard astronomy class, A. Robert Cole, '74, asked if he could produce a film as a substitute for writing a term paper. He and Bob Doyle learned of new synchronous sound Super8 movie systems being developed, like Bell and Howell Filmosound and the documentary filmmaker Richard Leacock's "double-system" sync sound project, funded by a $300,000 grant from Polaroid founder Edwin Land to Leacock's MIT department of Architecture and Film.

Bob applied to Harvard president Derek Bok for a $7500 grant to acquire an MIT/Leacock system for North House, where Cole was a student and Doyle a faculty associate. President Bok refused the grant, saying that every Harvard house would be wanting the same amount of money. While a momentary setback, it proved a long-term benefit, because it motivated Bob to develop some new technology and a business based on it.

Working with his brother in law, Wendl Thomis, a systems analyst and programmer at IBM, and with NASA physicist and neighbor Jordan "Jay" Kirsch, Bob Doyle modified a low-cost Sony TC800B tape recorder owned by Bob Cole to synchronize Super8 magnetic film with a Super8 camera. U.S. patent 3,900,251 was awarded for the Super8 Sound Recorder.

Bob prepared a full-page advertisement to run in the April 1973 issue of American Cinematographer magazine, the prestigious publication of the American Society of Cinematographers, the elite institution of Hollywood filmmakers. The initial reaction of the industry was that the amateur Super8 film format was not good enough for professional use. But Bob received four checks for $495 the week after the ad appeared. This was the initial starting capital for a new business he called Super8 Sound.

On the day the ad ran, Bob hired Julie Mamolen as a temporary secretary to share the Cambridge office where he was managing the Skylab collaborative observing program. She answered the phone as “Super8 Sound” and occasionally covered her receiver to ask Bob a question like “will we be selling a synchronizer?” Julie never asked the same question twice, learning everything about the company’s technology and the filmmaking industry in general as Vice President of Super8Sound.

Elected a full member of the sound engineering committee of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, Bob helped develop standards for one-pulse-per-frame digital synchronization signals between Super-8 film cameras, cassette tape recorders, and the Super8 Sound fullcoat magnetic film recorder.

Meanwhile, Ricky Leacock's MIT double-system was licensed to company Hamton Engineering for manufacture. It was sold around the world. Leacock personally delivered five MIT/Leacock systems to Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi. But there was a problem. When the sprocketed magnetic film was spliced, light leaking through the splice was interpreted as another frame of sound and the recorder lost synchronization with the picture. Buying five Super8 Sound Recorders eliminated the loss of synchronization.

Ricky Leacock said that Bob Doyle had "kicked him in the shins" but that together their work had established Super8 as the lowest cost sound film production medium.

In 1975, Bob prepared the first edition of the 72-page

Bob prepared a full-page advertisement to run in the April 1973 issue of American Cinematographer magazine, the prestigious publication of the American Society of Cinematographers, the elite institution of Hollywood filmmakers. The initial reaction of the industry was that the amateur Super8 film format was not good enough for professional use. But Bob received four checks for $495 the week after the ad appeared. This was the initial starting capital for a new business he called Super8 Sound.

On the day the ad ran, Bob hired Julie Mamolen as a temporary secretary to share the Cambridge office where he was managing the Skylab collaborative observing program. She answered the phone as “Super8 Sound” and occasionally covered her receiver to ask Bob a question like “will we be selling a synchronizer?” Julie never asked the same question twice, learning everything about the company’s technology and the filmmaking industry in general as Vice President of Super8Sound.

Elected a full member of the sound engineering committee of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers, Bob helped develop standards for one-pulse-per-frame digital synchronization signals between Super-8 film cameras, cassette tape recorders, and the Super8 Sound fullcoat magnetic film recorder.

Meanwhile, Ricky Leacock's MIT double-system was licensed to company Hamton Engineering for manufacture. It was sold around the world. Leacock personally delivered five MIT/Leacock systems to Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi. But there was a problem. When the sprocketed magnetic film was spliced, light leaking through the splice was interpreted as another frame of sound and the recorder lost synchronization with the picture. Buying five Super8 Sound Recorders eliminated the loss of synchronization.

Ricky Leacock said that Bob Doyle had "kicked him in the shins" but that together their work had established Super8 as the lowest cost sound film production medium.

In 1975, Bob prepared the first edition of the 72-page  Super8 Sound Catalog. It became the definitive equipment reference for Super8 filmmakers around the world. It went through three editions with an average circulation of 15,000 copies.

Super8 Sound grew quickly with seven dealers in the US and six more around the world in Australia, Benelux, Canada, France, Germany, and India. Sales of $52,000 in the final nine months of 1973 were followed by $250,000 in 1974, $530,000 in 1975, $650,000 in 1976, and $750,000 in 1977. Bob, Jay, and Wendl thought they might build one Super8 Sound Recorder a weekend in 1973, but instead Bob shipped over two thousand of them before he left the company to the employees in 1977.

Many thousands of budding filmmakers in the 1970's learned sync-sound filmmaking using low-cost "amateur" Super8 Sound tools. Decades later, many became Hollywood professionals. Bob called them "Super8 Professionals."

Despite the initially negative reputation of Super8 film, Super8 Sound Catalog. It became the definitive equipment reference for Super8 filmmakers around the world. It went through three editions with an average circulation of 15,000 copies.

Super8 Sound grew quickly with seven dealers in the US and six more around the world in Australia, Benelux, Canada, France, Germany, and India. Sales of $52,000 in the final nine months of 1973 were followed by $250,000 in 1974, $530,000 in 1975, $650,000 in 1976, and $750,000 in 1977. Bob, Jay, and Wendl thought they might build one Super8 Sound Recorder a weekend in 1973, but instead Bob shipped over two thousand of them before he left the company to the employees in 1977.

Many thousands of budding filmmakers in the 1970's learned sync-sound filmmaking using low-cost "amateur" Super8 Sound tools. Decades later, many became Hollywood professionals. Bob called them "Super8 Professionals."

Despite the initially negative reputation of Super8 film,  Hollywood's American Cinematographer magazine devoted their entire November 1975 issue to Professional Super 8 tools and technology developed by Bob at Super8 Sound. Herb Lightman, the Cinematographer editor, asked Bob to organize the whole issue. He solicited articles from industry experts and academics like Leacock's colleagues at MIT. Nothing could have validated Bob's work more than this testimony from the motion picture film world.

The legacy of Super8 Sound continues with worldwide support for the Super8 medium at Phil and Rhonda Vigeant's Pro8mm in California. Phil is called "the man who saved Super8." He was Super8 Sound's accountant and saved the company from potential financial collapse by taking charge of all company transactions and moving the company close to Hollywood.

Bob had shown he could build millions of dollars in film production tools, that he could create an international, if small, company and meet the payroll for a dozen employees, but sadly he had not shown he could make the profit needed to achieve financial independence and allow him to turn to studying physics and philosophy full-time.

Instead of running a manufacturing company, Bob imagined he might develop technology for licensing to a much larger company who would pay him royalties for his ideas?

Bob noticed that the transistor-transistor (TTL) logic circuits he used to servo-control the Super8 Sound Recorder in 1973 were being integrated into much larger chips called microprocessors, which could become the "central processing unit" (CPU) of a tiny computer - a "microcomputer." These microprocessors were expensive in 1974 (just under $20). Hollywood's American Cinematographer magazine devoted their entire November 1975 issue to Professional Super 8 tools and technology developed by Bob at Super8 Sound. Herb Lightman, the Cinematographer editor, asked Bob to organize the whole issue. He solicited articles from industry experts and academics like Leacock's colleagues at MIT. Nothing could have validated Bob's work more than this testimony from the motion picture film world.

The legacy of Super8 Sound continues with worldwide support for the Super8 medium at Phil and Rhonda Vigeant's Pro8mm in California. Phil is called "the man who saved Super8." He was Super8 Sound's accountant and saved the company from potential financial collapse by taking charge of all company transactions and moving the company close to Hollywood.

Bob had shown he could build millions of dollars in film production tools, that he could create an international, if small, company and meet the payroll for a dozen employees, but sadly he had not shown he could make the profit needed to achieve financial independence and allow him to turn to studying physics and philosophy full-time.

Instead of running a manufacturing company, Bob imagined he might develop technology for licensing to a much larger company who would pay him royalties for his ideas?

Bob noticed that the transistor-transistor (TTL) logic circuits he used to servo-control the Super8 Sound Recorder in 1973 were being integrated into much larger chips called microprocessors, which could become the "central processing unit" (CPU) of a tiny computer - a "microcomputer." These microprocessors were expensive in 1974 (just under $20).

But Gordon Moore, a founder of Intel Corporation, had formulated his famous "Moore's Law," that predicted prices would fall in half every year and a half, while doubling in computing power. Bob calculated that microprocessors should fall below $2 by 1977, so might be included in a game retailing for around $25.

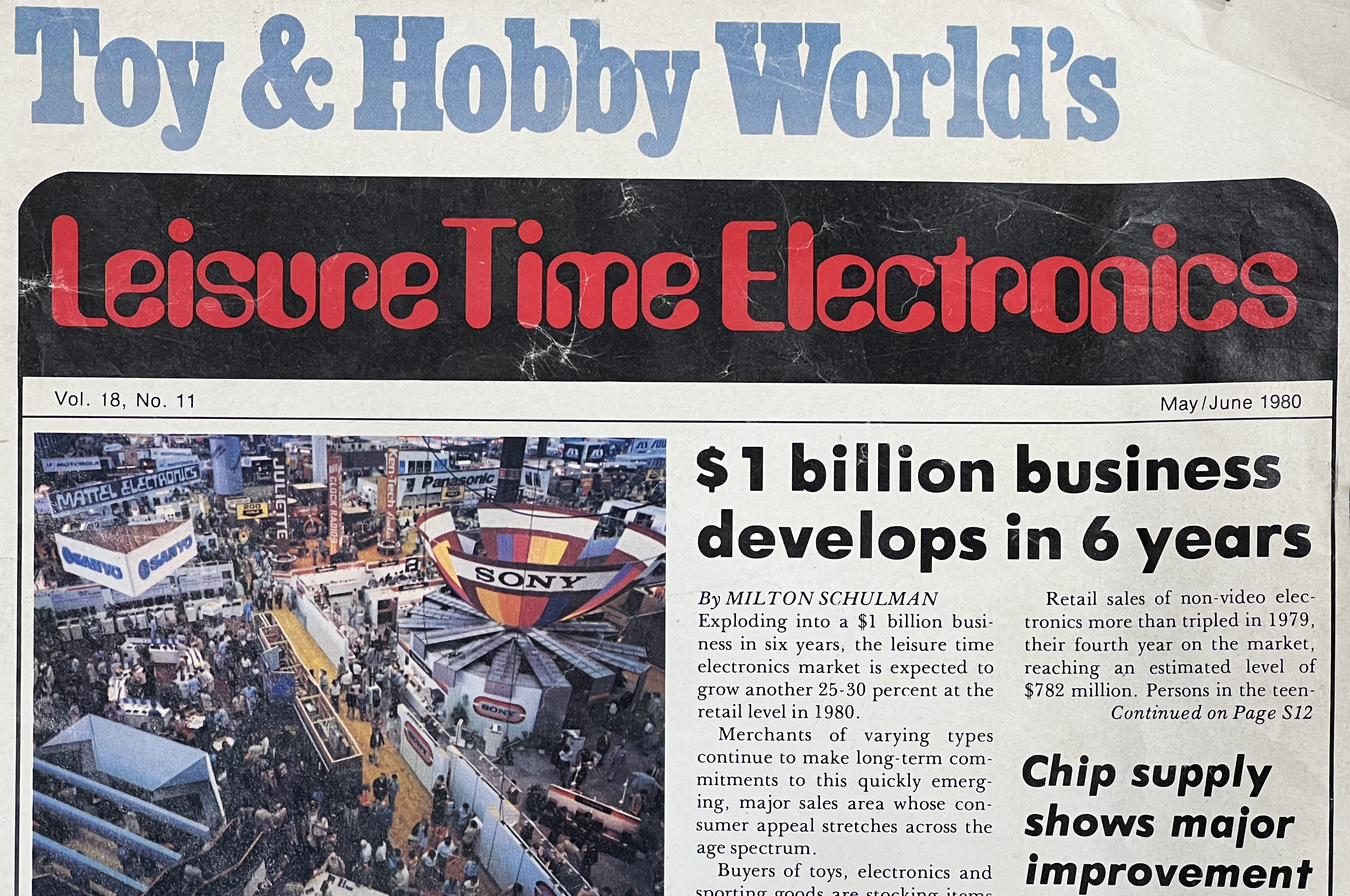

Bob wrote a letter in 1974 to the ten leading games companies and ten leading electronics companies, predicting there would be a $100 million-dollar-a-year electronic games business by the end of the decade. He was wrong by a factor of ten (though within so called "astrophysical accuracy"). In 1980 it was a billion-dollar industry and his games had a 25% market share.

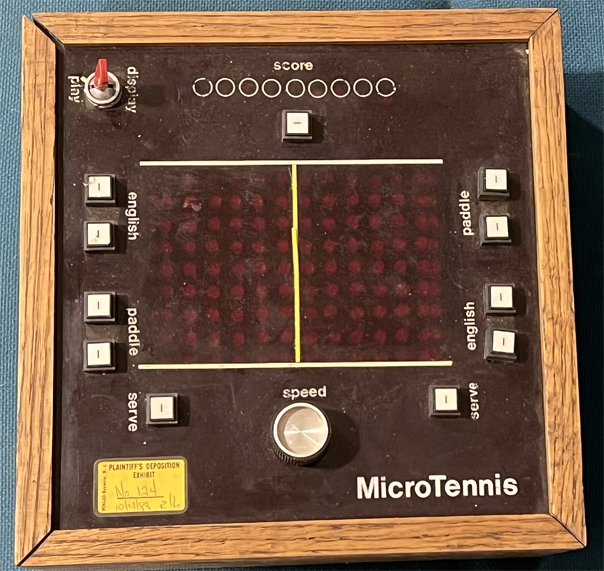

While he was full-time running Super8 Sound, Bob also worked again with brother-in-law Wendl Thomis, mostly on weekends, and now he enlisted his wife Holly Thomis Doyle to brain storm possible hand-held electronic or computer games. They called themselves "MicroCosmos" after a course called "MicroCosmos and MacroCosmos" Bob was teaching in the Harvard Extension School and in Harvard Summer School.

But Gordon Moore, a founder of Intel Corporation, had formulated his famous "Moore's Law," that predicted prices would fall in half every year and a half, while doubling in computing power. Bob calculated that microprocessors should fall below $2 by 1977, so might be included in a game retailing for around $25.

Bob wrote a letter in 1974 to the ten leading games companies and ten leading electronics companies, predicting there would be a $100 million-dollar-a-year electronic games business by the end of the decade. He was wrong by a factor of ten (though within so called "astrophysical accuracy"). In 1980 it was a billion-dollar industry and his games had a 25% market share.

While he was full-time running Super8 Sound, Bob also worked again with brother-in-law Wendl Thomis, mostly on weekends, and now he enlisted his wife Holly Thomis Doyle to brain storm possible hand-held electronic or computer games. They called themselves "MicroCosmos" after a course called "MicroCosmos and MacroCosmos" Bob was teaching in the Harvard Extension School and in Harvard Summer School.

They quickly identified a couple of dozen game ideas, including single-player games against the computer and a game for two players where the computer emulates a moving tennis ball. They then built working prototypes of four games, not yet using microprocessors but just that simple TTL logic. They showed the prototype games, based on arrays of light-emitting-diodes (LEDs), to several of those twenty companies. Every company asked them to sign "non-disclosure agreements" which gave the companies the rights to freely use any ideas they judged to be already known to the companies. As it turns out, many of the companies simply produced games modeled on those ideas without paying any royalties, but one company, Parker Brothers, proved to be upright and paid royalties for MicroCosmos games for several years. They published six out of twenty-five prototypes we built. They quickly identified a couple of dozen game ideas, including single-player games against the computer and a game for two players where the computer emulates a moving tennis ball. They then built working prototypes of four games, not yet using microprocessors but just that simple TTL logic. They showed the prototype games, based on arrays of light-emitting-diodes (LEDs), to several of those twenty companies. Every company asked them to sign "non-disclosure agreements" which gave the companies the rights to freely use any ideas they judged to be already known to the companies. As it turns out, many of the companies simply produced games modeled on those ideas without paying any royalties, but one company, Parker Brothers, proved to be upright and paid royalties for MicroCosmos games for several years. They published six out of twenty-five prototypes we built.

Parker Brothers published six MicroCosmos handheld computer games, including Code Name: Sector (1977), Merlin (1978), Wildfire (1979), Stop Thief (1979), P.E.G.S and Master Merlin (1980).

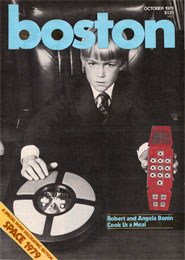

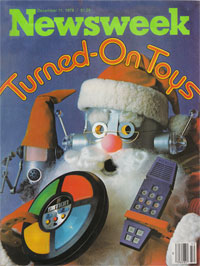

Merlin sold 5.5 million copies in 13 languages and was the most popular game or toy in the US in 1980, according to the Toy Manufacturers of America. Merlin was on the October 1978 cover of Boston Magazine and the December 1978 cover of Newsweek magazine.

Merlin lives on today online at theelectronicwizard.com, thanks to a program written by Bob's son Derek in Javascript. Children around the world can play Merlin's six games without owning a physical version.

In retrospect, Bob should probably have stopped at this point and turned to his problems in physics and philosophy, having generated all the wealth he really needed to become a full-time philosopher of science.

Parker Brothers published six MicroCosmos handheld computer games, including Code Name: Sector (1977), Merlin (1978), Wildfire (1979), Stop Thief (1979), P.E.G.S and Master Merlin (1980).

Merlin sold 5.5 million copies in 13 languages and was the most popular game or toy in the US in 1980, according to the Toy Manufacturers of America. Merlin was on the October 1978 cover of Boston Magazine and the December 1978 cover of Newsweek magazine.

Merlin lives on today online at theelectronicwizard.com, thanks to a program written by Bob's son Derek in Javascript. Children around the world can play Merlin's six games without owning a physical version.

In retrospect, Bob should probably have stopped at this point and turned to his problems in physics and philosophy, having generated all the wealth he really needed to become a full-time philosopher of science.

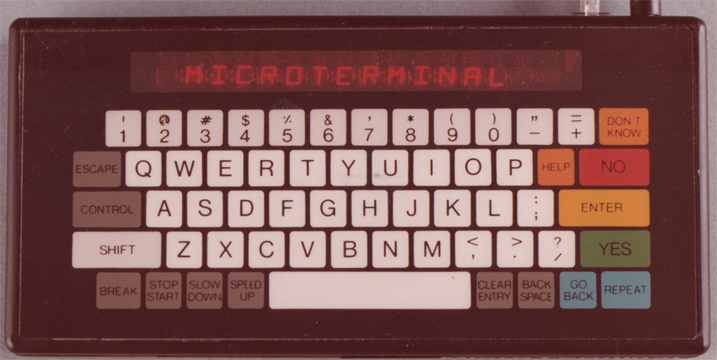

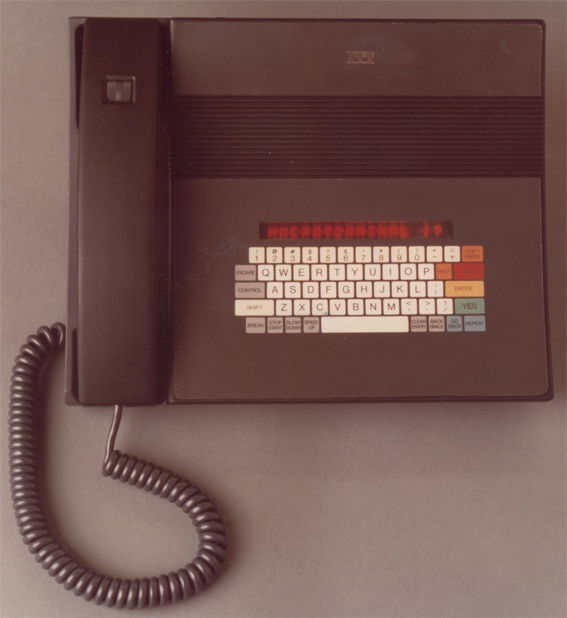

But in 1979, Bob developed a handheld personal computer terminal he initially called a "microterminal" to access airline reservations, banking, stock trading, and many future online services. It was based on a wordplay game with a 16-character display and an alphanumeric keyboard, one of several dozen possible computer games the MicroCosmos team had imagined.

But in 1979, Bob developed a handheld personal computer terminal he initially called a "microterminal" to access airline reservations, banking, stock trading, and many future online services. It was based on a wordplay game with a 16-character display and an alphanumeric keyboard, one of several dozen possible computer games the MicroCosmos team had imagined.

Bob presented working prototypes of the microterminal to dozens of computer companies and communications companies, such as IBM, AT&T, GT&E, and IT&T. GT&E paid $150,000 for a 3-month exclusive license to the technology in the US and IT&T flew Bob and Holly to Brussels to discuss international rights to the technology. They brought a microterminal prototype encased in an elegant European-stye telephone, plugged it in to some ancient telephone wiring in IT&T headquarters, and demonstrated simulations of services like airline reservations and stock trades, running on a microcomputer across the Atlantic at Bob's lab back in Cambridge, MA. The software simulations were written by Bob, his elder son Rob, and Rob's computer friends.

But just as licensing an idea to games companies was problematic and likely unrealistic (with Parker Brothers the exception), licensing the microterminal was also likely doomed. Bill Enders, a vice president of GT&E, told Bob some time after the exclusive license agreement expired, that GT&E President Thomas Vanderslice had actually authorized $250,000 for the license, but he (Enders) had offered Bob only $150,000, expecting Bob to negotiate. He was surprised that Bob naively jumped at the offer. Enders also told Bob that Vanderslice had ordered GTE Labs to find ways around any royalty payments. Lessons learned about negotiating with big business!

Another of the companies who saw the MicroCosmos prototypes was Mattel Electronics, a division of Mattel, Inc. The electronics division was created by Jeff Rochlis, who started it with a secretary and one electronics engineer. He had grown it by 1980 into a $250 million business, with a 1980 market share similar to Parker Brothers. Rochlis and Mattel vice president Ed Krakauer visited Bob's lab for a microterminal demonstration. Rochlis saw a great potential market for a handheld device that connected to the telephone network to access services like banking, paying bills, stock trading, and airline reservations.

Rochlis expressed interest in joining Bob in this project and Bob offered Jeff ten percent of a future company, which Bob was calling IO (for input/output and one/zero). Jeff jumped at the offer (without negotiating) and left Mattel (as did Krakauer to form General Consumer Electronics). Jeff looked into the agreements with GTE and IT&T and was skeptical. He arranged a meeting with the business consultants Arthur D. Little to explore options. ADL strongly recommended that the new company seek venture capital.

Over the next few months, Jeff and Bob met with several venture capital firms. A group of firms, led by Five Arrows (part of Rothschild and Co.), including Fidelity Investments, First Bank of Boston, and General Instruments, offered $3,500,000 for 35% of the new company, which Jeff renamed IXO. At that time, with the new company valued at ten million dollars and Bob's share of stock about one-third of the total, he might well have felt secure enough to turn to physics and philosophy?

Bob presented working prototypes of the microterminal to dozens of computer companies and communications companies, such as IBM, AT&T, GT&E, and IT&T. GT&E paid $150,000 for a 3-month exclusive license to the technology in the US and IT&T flew Bob and Holly to Brussels to discuss international rights to the technology. They brought a microterminal prototype encased in an elegant European-stye telephone, plugged it in to some ancient telephone wiring in IT&T headquarters, and demonstrated simulations of services like airline reservations and stock trades, running on a microcomputer across the Atlantic at Bob's lab back in Cambridge, MA. The software simulations were written by Bob, his elder son Rob, and Rob's computer friends.

But just as licensing an idea to games companies was problematic and likely unrealistic (with Parker Brothers the exception), licensing the microterminal was also likely doomed. Bill Enders, a vice president of GT&E, told Bob some time after the exclusive license agreement expired, that GT&E President Thomas Vanderslice had actually authorized $250,000 for the license, but he (Enders) had offered Bob only $150,000, expecting Bob to negotiate. He was surprised that Bob naively jumped at the offer. Enders also told Bob that Vanderslice had ordered GTE Labs to find ways around any royalty payments. Lessons learned about negotiating with big business!

Another of the companies who saw the MicroCosmos prototypes was Mattel Electronics, a division of Mattel, Inc. The electronics division was created by Jeff Rochlis, who started it with a secretary and one electronics engineer. He had grown it by 1980 into a $250 million business, with a 1980 market share similar to Parker Brothers. Rochlis and Mattel vice president Ed Krakauer visited Bob's lab for a microterminal demonstration. Rochlis saw a great potential market for a handheld device that connected to the telephone network to access services like banking, paying bills, stock trading, and airline reservations.

Rochlis expressed interest in joining Bob in this project and Bob offered Jeff ten percent of a future company, which Bob was calling IO (for input/output and one/zero). Jeff jumped at the offer (without negotiating) and left Mattel (as did Krakauer to form General Consumer Electronics). Jeff looked into the agreements with GTE and IT&T and was skeptical. He arranged a meeting with the business consultants Arthur D. Little to explore options. ADL strongly recommended that the new company seek venture capital.

Over the next few months, Jeff and Bob met with several venture capital firms. A group of firms, led by Five Arrows (part of Rothschild and Co.), including Fidelity Investments, First Bank of Boston, and General Instruments, offered $3,500,000 for 35% of the new company, which Jeff renamed IXO. At that time, with the new company valued at ten million dollars and Bob's share of stock about one-third of the total, he might well have felt secure enough to turn to physics and philosophy?

The IXO Telecomputing System was cited for "human factors engineering" on the cover of BYTE magazine in April 1982 and in an INC magazine article on Bob's electronic games and the telecomputer in September 1982. But the operations of IXO were not going well. The new president of IXO had hired 65 employees of his former Mattel Electronics division and quartered them in a first-class office space overlooking the water in San Marino. Rochlis was burning through the venture capital, necessitating second and third rounds at increasingly unfavorable terms. By 1984, Bob's stock had been reduced to about 1% of the company. More lessons learned about business.

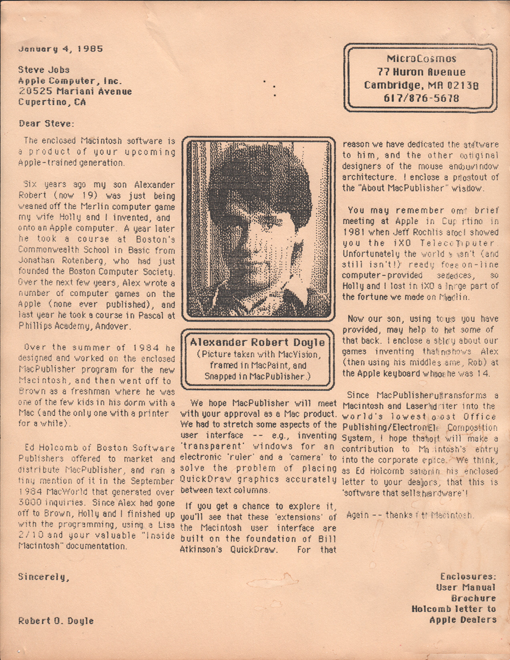

Removed from the day-to-day development of the microterminal, now telecomputer, Bob did turn to the idea of publishing his scientific and philosophical ideas. Skeptical of finding a major publisher, and hearing of independent thinkers "self-publishing," he imagined he might write a software program that would support publishing with one of the new personal computers. Bob had previously met with Steve Jobs to discuss licensing the IXO telecomputer technology as a potential Apple "Blueberry." And in 1984, Jobs had introduced the new Apple Macintosh computer, with a "what-you-see-is-what-you-get" visual interface that could support multiple columns of type needed to layout a newspaper. The development language for the Macintosh was Pascal. Bill Atkinson had developed a "Pascal Toolbox" of primitive routines for graphic elements. Bill's toolbox provided the structure for MacPaint. Bob bought and avidly read the multiple volumes of the documentation "Inside Macintosh," and applied to Apple for developer status. He was accepted as the eleventh certified outside developer.

The IXO Telecomputing System was cited for "human factors engineering" on the cover of BYTE magazine in April 1982 and in an INC magazine article on Bob's electronic games and the telecomputer in September 1982. But the operations of IXO were not going well. The new president of IXO had hired 65 employees of his former Mattel Electronics division and quartered them in a first-class office space overlooking the water in San Marino. Rochlis was burning through the venture capital, necessitating second and third rounds at increasingly unfavorable terms. By 1984, Bob's stock had been reduced to about 1% of the company. More lessons learned about business.

Removed from the day-to-day development of the microterminal, now telecomputer, Bob did turn to the idea of publishing his scientific and philosophical ideas. Skeptical of finding a major publisher, and hearing of independent thinkers "self-publishing," he imagined he might write a software program that would support publishing with one of the new personal computers. Bob had previously met with Steve Jobs to discuss licensing the IXO telecomputer technology as a potential Apple "Blueberry." And in 1984, Jobs had introduced the new Apple Macintosh computer, with a "what-you-see-is-what-you-get" visual interface that could support multiple columns of type needed to layout a newspaper. The development language for the Macintosh was Pascal. Bill Atkinson had developed a "Pascal Toolbox" of primitive routines for graphic elements. Bill's toolbox provided the structure for MacPaint. Bob bought and avidly read the multiple volumes of the documentation "Inside Macintosh," and applied to Apple for developer status. He was accepted as the eleventh certified outside developer.

In just a few months, Bob wrote what he called an "electronic publishing" program for the Macintosh, with a lot of help from wife Holly and sons Rob and Derek. He named it MacPublisher. It was one of the few software programs introduced in the same year as the 128K Macintosh. Bob printed a 3-column letter on the dot-matrix ink-jet Apple ImageWriter and sent it to Steve in January, 1985, arguing that electronic publishing would become "software that sells hardware."

In that same month, Apple released the Laserwriter, replacing the crude dot-matrix print quality with fine typefaces. This combination of software and hardware triggered a publishing revolution. Paul Brainerd, a vice president at Atex, whose several-thousand-dollar electronic publishing system was used by major magazines and newspapers, founded the Aldus Corporation and introduced PageMaker, for the 1985 512K "Big Mac." Brainerd called the new field "desktop publishing." PageMaker was later sold to Adobe, who replaced it with the InDesign desktop publishing tool that Bob uses everyday to layout his books.

After selling about ten thousand copies of MacPublisher for $99, Bob sold the program to Esselte Letraset for $500,000 plus a three-year contract for five days of consulting each year at $10,000 per day. Once again, Bob had the financial strength and now the tools to publish his philosophical ideas, but he continued to be seduced by technology developments. In just a few months, Bob wrote what he called an "electronic publishing" program for the Macintosh, with a lot of help from wife Holly and sons Rob and Derek. He named it MacPublisher. It was one of the few software programs introduced in the same year as the 128K Macintosh. Bob printed a 3-column letter on the dot-matrix ink-jet Apple ImageWriter and sent it to Steve in January, 1985, arguing that electronic publishing would become "software that sells hardware."

In that same month, Apple released the Laserwriter, replacing the crude dot-matrix print quality with fine typefaces. This combination of software and hardware triggered a publishing revolution. Paul Brainerd, a vice president at Atex, whose several-thousand-dollar electronic publishing system was used by major magazines and newspapers, founded the Aldus Corporation and introduced PageMaker, for the 1985 512K "Big Mac." Brainerd called the new field "desktop publishing." PageMaker was later sold to Adobe, who replaced it with the InDesign desktop publishing tool that Bob uses everyday to layout his books.

After selling about ten thousand copies of MacPublisher for $99, Bob sold the program to Esselte Letraset for $500,000 plus a three-year contract for five days of consulting each year at $10,000 per day. Once again, Bob had the financial strength and now the tools to publish his philosophical ideas, but he continued to be seduced by technology developments.

In 1988, Bob provided financing for Matt and Patrice York to launch Videomaker Magazine. Matt had been a Super8 Sound customer and noted that when Super8 Filmaker magazine was launched there were only a few hundred thousand Super8 film cameras, but there was as yet no magazine for videomakers, despite over a million video cameras sold that year.

In the early 1990's Bob was invited to become the "digital video guru" for NewMedia magazine, which had a quarter million subscribers. He formed "NewMedia Lab" where he tested and reported on all the latest developments in consumer video, especially its evolution from analog to digital video camcorders, and the creation of "desktop video" non-linear editing systems like Adobe Premiere, Avid Media Composer, and Media 100. He formed a "desktop video group," which met monthly at his lab and grew to over 150 members.

Leading non-linear editing providers like Avid let Bob keep the "beta" versions he tested and he gave them to media institutions in the Boston area, including Boston Film/Video Foundation, Cambridge Community Television, and Massachusetts College of Art.

In the late nineties, Bob was greatly inspired by MIT Professor Philip Greenspun's books Database Backed Websites: The Thinking Person's Guide to Web Publishing and Philip & Alex's Guide to Web Publishing.

Bob began to think about developing a web publishing tool that would build on his original ideas for desktop publishing.

Bob also read BYTE magazine editor Jon Udell's 1999 book Practical Internet Groupware, which suggested that Bob and his son Derek could make a collaborative editing tool that would allow philosophers and scientists to contribute to the website in the future.

But perhaps the most important book that influenced the design of Bob's web publishing software, which Bob and Derek called "TimeLines," was Weaving the Web: The Original Design and Ultimate Destiny of the World Wide Web, by the inventor of the web, Sir Tim Berners-Lee.

Bob and Derek met with Berners-Lee at MIT in late 2000 and described their web publishing plans. Berners-Lee told them his greatest disappointment about the web was visiting a URL he had saved for a valuable web page only to find it had disappeared from the web. He said he was working on a proposal for a "persistent archive" of web pages. Tim took Bob's copy of Weaving the Web and inscribed the address for his proposal for persistent domains inside the back cover. Derek studied it and within a few weeks had a working version. You can see the persistent archive for the I-Phi home page at this address informationphilosopher.com/index.parc.html

Derek recently added the ability to travel in time through the I-Phi web pages by clicking the @ key (shift-2). you can then enter any date and time and see the page then being served. Tim Berners-Lee also proposed that pages could be versioned for different languages.

In 2003, Bob helped NPR radio show host Christopher Lydon and software development engineer Dave Winer create the first "podcasts" at Harvard's Berkman Center, where Winer was a research associate and had created the first Harvard faculty blogs. Winer recently posted an archive of those early podcasts.

In 1988, Bob provided financing for Matt and Patrice York to launch Videomaker Magazine. Matt had been a Super8 Sound customer and noted that when Super8 Filmaker magazine was launched there were only a few hundred thousand Super8 film cameras, but there was as yet no magazine for videomakers, despite over a million video cameras sold that year.

In the early 1990's Bob was invited to become the "digital video guru" for NewMedia magazine, which had a quarter million subscribers. He formed "NewMedia Lab" where he tested and reported on all the latest developments in consumer video, especially its evolution from analog to digital video camcorders, and the creation of "desktop video" non-linear editing systems like Adobe Premiere, Avid Media Composer, and Media 100. He formed a "desktop video group," which met monthly at his lab and grew to over 150 members.

Leading non-linear editing providers like Avid let Bob keep the "beta" versions he tested and he gave them to media institutions in the Boston area, including Boston Film/Video Foundation, Cambridge Community Television, and Massachusetts College of Art.

In the late nineties, Bob was greatly inspired by MIT Professor Philip Greenspun's books Database Backed Websites: The Thinking Person's Guide to Web Publishing and Philip & Alex's Guide to Web Publishing.

Bob began to think about developing a web publishing tool that would build on his original ideas for desktop publishing.

Bob also read BYTE magazine editor Jon Udell's 1999 book Practical Internet Groupware, which suggested that Bob and his son Derek could make a collaborative editing tool that would allow philosophers and scientists to contribute to the website in the future.

But perhaps the most important book that influenced the design of Bob's web publishing software, which Bob and Derek called "TimeLines," was Weaving the Web: The Original Design and Ultimate Destiny of the World Wide Web, by the inventor of the web, Sir Tim Berners-Lee.

Bob and Derek met with Berners-Lee at MIT in late 2000 and described their web publishing plans. Berners-Lee told them his greatest disappointment about the web was visiting a URL he had saved for a valuable web page only to find it had disappeared from the web. He said he was working on a proposal for a "persistent archive" of web pages. Tim took Bob's copy of Weaving the Web and inscribed the address for his proposal for persistent domains inside the back cover. Derek studied it and within a few weeks had a working version. You can see the persistent archive for the I-Phi home page at this address informationphilosopher.com/index.parc.html

Derek recently added the ability to travel in time through the I-Phi web pages by clicking the @ key (shift-2). you can then enter any date and time and see the page then being served. Tim Berners-Lee also proposed that pages could be versioned for different languages.

In 2003, Bob helped NPR radio show host Christopher Lydon and software development engineer Dave Winer create the first "podcasts" at Harvard's Berkman Center, where Winer was a research associate and had created the first Harvard faculty blogs. Winer recently posted an archive of those early podcasts.

(Click for an expandable panoramic view of Winer's BloggerCon. Dave Winer is on the left. Chris Lydon is the soundman in the center and Bob Doyle is recording video in the front row). Since Super8 Sound, Bob has spent much of his life building tools, he says, to "put the means of production in the hands of the people," not as Karl Marx imagined by nationalizing them, but by basing them on low-cost consumer products to make them affordable, even free and "open source." He has been adapting consumer devices to reduce the cost of film and video tools for nearly fifty years to "help communities communicate." Bob has provided technical, logistic, and financial support to many individuals and media groups in the Boston area, including the Boston Cyberarts Festival, Boston Film/Video Foundation, Cambridge Community Television, Harvard Radcliffe Television, Harvard's Quad Sound Studios, and the Harvard Crimson. The iTV-Studio is a research and development project by Bob that is another technology distraction, but it was built to support Bob's lectures streaming on YouTube and cablecast daily on CCTV in Cambridge.  This iTV-Studio is a one-person operation. While lecturing, Bob switches between 7 Sony PTZ cameras and three media sources (two PCs and two Microsoft Surface Pros that display his web pages, including YouTube videos, and online Skype guests), using the Blackmagic Design ATEM switcher app on an iPad Pro.

This iTV-Studio is a one-person operation. While lecturing, Bob switches between 7 Sony PTZ cameras and three media sources (two PCs and two Microsoft Surface Pros that display his web pages, including YouTube videos, and online Skype guests), using the Blackmagic Design ATEM switcher app on an iPad Pro.

Behind these are four DisplayLink screens extending his desktops. To his left on a pull-out drawer are the Sony PTZ camera controller, a laptop PC running his teleprompter software, an audio mixer, and the ATEM multiview screen on the table. The PTZ controller has multiple presets for the seven cameras. To his right on a pull-out drawer are three iPads running the Teradek VidiU app and Teradek Core streaming simultaneously to YouTube and to CCTV cable television in Cambridge.

Behind these are four DisplayLink screens extending his desktops. To his left on a pull-out drawer are the Sony PTZ camera controller, a laptop PC running his teleprompter software, an audio mixer, and the ATEM multiview screen on the table. The PTZ controller has multiple presets for the seven cameras. To his right on a pull-out drawer are three iPads running the Teradek VidiU app and Teradek Core streaming simultaneously to YouTube and to CCTV cable television in Cambridge.

Information Philosopher Website

Bob's goal for the I-Phi website is to provide web pages on all the major philosophers and scientists who have worked on the problems of freedom, value, and knowledge. Each page has excerpts from the thinker's work and a critical analysis. The original three major sections of the website each have a history of the problem, the relevant physics, biology, cosmology, etc, and pages on the core concepts of the problem. In recent years, sections have been added on the mind, life, chance, and quantum entanglement.

As mentioned, Bob and his son Derek wrote a "web publishing program" they called "TimeLines" to implement Tim Berners-Lee's concept of a persistent archive. You can test "TimeLines" by pressing the @ key (shift-2) on any of the I-Phi pages. Berners-Lee also suggested that a website could provide translations of its pages in multiple languages. Since the I-Phi website has readers from many parts of the world, it uses Google Translate to provide "gists" of all pages. Once you click on a new language, all the hyperlinks to other pages are automatically translated as you navigate through the I-Phi hyperspace. A languages drop-down menu offers five European languages and some pages (like this, see page bottom) offer twelve translation languages.

In 2016, Bob launched Metaphysicist.com to show how information philosophy can solve many problems, puzzles, and paradoxes in metaphysics. As opposed to metaphysicians, who are today mostly analytic language philosophers, a metaphysicist can show that information is physical, but immaterial. Thoughts in minds are immaterial, yet they causally influence the actions of the material brain and body.

Bob had the great privilege of working with some of the world's leading philosophers of the free will problem starting in 2009, when his first published philosophy appeared in Nature.

A paper in William James Studies on the two-stage free-will model of William James got Bob an invitation to the William James Symposium at Harvard in August, 2010 to present a 90-minute seminar (available on YouTube) on James' ideas on free will, along with the similar ideas of a dozen scientists and philosophers since James. Since 2010, another dozen thinkers have been discovered who support Bob's two-stage model of free will, which first was described in James' 1884 essay, "The Dilemma of Determinism."

The compatibilist philosopher Daniel Dennett invited Bob to take part in his graduate seminar on free will at Tufts in the Fall of 2010. He submitted many short papers to the seminar on his positions relative to Dennett's view that free will is "compatible" with physical determinism and a single possible future. In his 1978 book Brainstorms, Dennett had offered a two-stage model of free will for consideration by libertarian thinkers (though doubting it himself), but for years he resisted Bob's argument that the first stage should involve quantum indeterminism. In a pleasant surprise, shortly before his death in April 2018, Dennett described on a YouTube video that he had come to accept Bob's two-stage model with quantum indeterminism.

Bob was invited to present his two-stage model of free will at an "Experts Meeting" on Free Will at the Social Trends Institute in Barcelona, Spain in October, 2010, along with Robert Kane, editor of the Oxford Handbook on Free Will, Alfred Mele, who directed a program at Florida State University that studied free will with a $4.4 million grant from the Templeton Foundation, and Martin Heisenberg (a son of Werner Heisenberg), who claimed in Nature that even the lowest animals have a kind of "behavioral freedom." They are not biological machines reacting deterministically to stimuli with programmed responses. They originate actions, stochastically.

Bob sent a letter to Nature commenting on Heisenberg's article. It was published in June 2009 as "Free will: it’s a normal biological property, not a gift or a mystery." This was his first philosophical publication.

The Two-Stage Solution to the Problem of Free Will,” was published in Is Science Compatible with Free Will?: Exploring Free Will and Consciousness in the Light of Quantum Physics and Neuroscience, (2012) Springer Verlag.

In February, 2011, Bob Kane encouraged Bob to turn the Freedom section of this website into a book, which he did amazingly quickly, thanks to Adobe InDesign and a print-on-demand service at the Harvard Book Store in Harvard Square that produced 14 revisions in as many weeks.

Bob's first philosophy book - Free Will: The Scandal in Philosophy - was published on June 19, 2011, his 75th birthday. It is available on Amazon and Barnes & Noble, along with eBook versions for the Kindle and Nook.

His second book - Great Problems in Philosophy and Physics Solved? - was published on September 15, 2016. HIs third - Metaphysics Problems , Puzzles, and Paradoxes Solved? - appeared in December 2016. They are both available on Amazon.

His fourth book - My God, He Plays Dice! - How Albert Einstein Invented Most of Quantum Mechanics was published in 2019.

A fifth book written by David Layzer, Bob's mentor at Harvard and his wife Holly's thesis adviser, was edited by Bob and published in 2021, two years after Layzer's death. In the book, Why We are Free, Layzer describes the importance of the alternative possibilities underlying his idea of free will, which he bases on a "primordial randomness." Layzer saw this randomness as an alternative to the quantum randomness and the source of freedom from philosophical determinism.

All Bob's books are available as free PDF downloads on the I-Phi website.

In addition to his extensive websites (this one and metaphysicist.com) and his printed books, Bob produced fifty lectures on his YouTube channel and Facebook page.

Bob's email is bobdoyle@informationphilosopher.com.

His address and phone number are:77 Huron Avenue Cambridge, Mass 02138 617-876-5678 Skype handle:bobdoyle YouTube channel: infophilosopher Twitter username: infophilosopher Facebook page: infophilosopher I-Phi Blog: i-phi.org Bob is an Associate in the Astronomy Department, Harvard University His faculty email is rodoyle@fas.harvard.edu

Bob's philosophical publications

Robert O. Doyle, "Free Will: it’s a normal biological property, not a gift or a mystery," Nature, 459, June 2009, p.1052.

A ten-minute animated tutorial on the Two-Stage Model for Free Will

Robert O. Doyle, "Jamesian Free Will: The Two-Stage Model of William James," William James Studies, June, 2010

Powerpoint presentation at the William James Symposium, August 28, 2010.

Videos of the presentation at William James Symposium:

Two Steps to Free Will, Harvard Magazine, July-August 2012. Mente e Libertà? (Mind and Freedom?), Interview, Avvenire, June 4, 2013. Quantum Physics and the Problem of Mental Causation, presented in Milan, June 6, 2013, at a conference on "Quantum Physics and the Philosophy of Mind." (Slides)  480 pages, 40 figures, 15 sidebars, bibliography, glossary, index. Philosophers who want to review it can download a PDF or an eBook. PDFs of the individual chapters are here.Great Problems in Philosophy (and Physics) Solved? was published in September 2016 472 pages, 45 figures, bibliography, index. Philosophers who want to review it can download a PDF or an eBook. PDFs of the individual chapters are here.Metaphysics: Problems, Paradoxes, and Puzzles Solved? was published in December 2016 428 pages, 13 figures, bibliography, index. Philosophers who want to review it can download a PDF or an eBook. PDFs of the individual chapters are here.My God, He Plays Dice! How Albert Einstein Invented Most of Quantum Mechanics, was published in March, 2019 452 pages, 71 figures, bibliography, index. PDFs of the draft chapters are here.His fifth book Bob did not write. He was an editor for David Layzer's book on free will. He did co-write a preface and afterword with Anthony Aguirre. In this book Bob's Harvard colleague and mentor Layzer answers Bob's fundamental question of information philosophy", Why We are Free was published in March, 2021 168 pages pages, 4 figures, bibliography, index. An interactive PDF of the book is here. Paperback and Kindle versions are here

Bob on his philosophical background

My life-long love of philosophy began over sixty-five years ago with undergraduate courses at Brown University which were required for my degree in Physics. A course in Ethics made the biggest impression, especially its conclusion that science has absolutely nothing to contribute to the subject. Ethical values must be found in traditional sources like religion and secular humanism. This struck me as odd. As Bertrand Russell had written, "What science cannot discover, mankind cannot know.”