|

Topics

Introduction

Problems Freedom Knowledge Mind Life Chance Quantum Entanglement Scandals Philosophers Mortimer Adler Rogers Albritton Alexander of Aphrodisias Samuel Alexander William Alston Anaximander G.E.M.Anscombe Anselm Louise Antony Thomas Aquinas Aristotle David Armstrong Harald Atmanspacher Robert Audi Augustine J.L.Austin A.J.Ayer Alexander Bain Mark Balaguer Jeffrey Barrett William Barrett William Belsham Henri Bergson George Berkeley Isaiah Berlin Richard J. Bernstein Bernard Berofsky Robert Bishop Max Black Susan Blackmore Susanne Bobzien Emil du Bois-Reymond Hilary Bok Laurence BonJour George Boole Émile Boutroux Daniel Boyd F.H.Bradley C.D.Broad Michael Burke Jeremy Butterfield Lawrence Cahoone C.A.Campbell Joseph Keim Campbell Rudolf Carnap Carneades Nancy Cartwright Gregg Caruso Ernst Cassirer David Chalmers Roderick Chisholm Chrysippus Cicero Tom Clark Randolph Clarke Samuel Clarke Anthony Collins August Compte Antonella Corradini Diodorus Cronus Jonathan Dancy Donald Davidson Mario De Caro Democritus William Dembski Brendan Dempsey Daniel Dennett Jacques Derrida René Descartes Richard Double Fred Dretske Curt Ducasse John Earman Laura Waddell Ekstrom Epictetus Epicurus Austin Farrer Herbert Feigl Arthur Fine John Martin Fischer Frederic Fitch Owen Flanagan Luciano Floridi Philippa Foot Alfred Fouilleé Harry Frankfurt Richard L. Franklin Bas van Fraassen Michael Frede Gottlob Frege Peter Geach Edmund Gettier Carl Ginet Alvin Goldman Gorgias Nicholas St. John Green Niels Henrik Gregersen H.Paul Grice Ian Hacking Ishtiyaque Haji Stuart Hampshire W.F.R.Hardie Sam Harris William Hasker R.M.Hare Georg W.F. Hegel Martin Heidegger Heraclitus R.E.Hobart Thomas Hobbes David Hodgson Shadsworth Hodgson Baron d'Holbach Ted Honderich Pamela Huby David Hume Ferenc Huoranszki Frank Jackson William James Lord Kames Robert Kane Immanuel Kant Tomis Kapitan Walter Kaufmann Jaegwon Kim William King Hilary Kornblith Christine Korsgaard Saul Kripke Thomas Kuhn Andrea Lavazza James Ladyman Christoph Lehner Keith Lehrer Gottfried Leibniz Jules Lequyer Leucippus Michael Levin Joseph Levine George Henry Lewes C.I.Lewis David Lewis Peter Lipton C. Lloyd Morgan John Locke Michael Lockwood Arthur O. Lovejoy E. Jonathan Lowe John R. Lucas Lucretius Alasdair MacIntyre Ruth Barcan Marcus Tim Maudlin James Martineau Nicholas Maxwell Storrs McCall Hugh McCann Colin McGinn Michael McKenna Brian McLaughlin John McTaggart Paul E. Meehl Uwe Meixner Alfred Mele Trenton Merricks John Stuart Mill Dickinson Miller G.E.Moore Ernest Nagel Thomas Nagel Otto Neurath Friedrich Nietzsche John Norton P.H.Nowell-Smith Robert Nozick William of Ockham Timothy O'Connor Parmenides David F. Pears Charles Sanders Peirce Derk Pereboom Steven Pinker U.T.Place Plato Karl Popper Porphyry Huw Price H.A.Prichard Protagoras Hilary Putnam Willard van Orman Quine Frank Ramsey Ayn Rand Michael Rea Thomas Reid Charles Renouvier Nicholas Rescher C.W.Rietdijk Richard Rorty Josiah Royce Bertrand Russell Paul Russell Gilbert Ryle Jean-Paul Sartre Kenneth Sayre T.M.Scanlon Moritz Schlick John Duns Scotus Albert Schweitzer Arthur Schopenhauer John Searle Wilfrid Sellars David Shiang Alan Sidelle Ted Sider Henry Sidgwick Walter Sinnott-Armstrong Peter Slezak J.J.C.Smart Saul Smilansky Michael Smith Baruch Spinoza L. Susan Stebbing Isabelle Stengers George F. Stout Galen Strawson Peter Strawson Eleonore Stump Francisco Suárez Richard Taylor Kevin Timpe Mark Twain Peter Unger Peter van Inwagen Manuel Vargas John Venn Kadri Vihvelin Voltaire G.H. von Wright David Foster Wallace R. Jay Wallace W.G.Ward Ted Warfield Roy Weatherford C.F. von Weizsäcker William Whewell Alfred North Whitehead David Widerker David Wiggins Bernard Williams Timothy Williamson Ludwig Wittgenstein Susan Wolf Xenophon Scientists David Albert Philip W. Anderson Michael Arbib Bobby Azarian Walter Baade Bernard Baars Jeffrey Bada Leslie Ballentine Marcello Barbieri Jacob Barandes Julian Barbour Horace Barlow Gregory Bateson Jakob Bekenstein John S. Bell Mara Beller Charles Bennett Ludwig von Bertalanffy Susan Blackmore Margaret Boden David Bohm Niels Bohr Ludwig Boltzmann John Tyler Bonner Emile Borel Max Born Satyendra Nath Bose Walther Bothe Jean Bricmont Hans Briegel Leon Brillouin Daniel Brooks Stephen Brush Henry Thomas Buckle S. H. Burbury Melvin Calvin William Calvin Donald Campbell John O. Campbell Sadi Carnot Sean B. Carroll Anthony Cashmore Eric Chaisson Gregory Chaitin Jean-Pierre Changeux Rudolf Clausius Arthur Holly Compton John Conway Simon Conway-Morris Peter Corning George Cowan Jerry Coyne John Cramer Francis Crick E. P. Culverwell Antonio Damasio Olivier Darrigol Charles Darwin Paul Davies Richard Dawkins Terrence Deacon Lüder Deecke Richard Dedekind Louis de Broglie Stanislas Dehaene Max Delbrück Abraham de Moivre David Depew Bernard d'Espagnat Paul Dirac Theodosius Dobzhansky Hans Driesch John Dupré John Eccles Arthur Stanley Eddington Gerald Edelman Paul Ehrenfest Manfred Eigen Albert Einstein George F. R. Ellis Walter Elsasser Hugh Everett, III Franz Exner Richard Feynman R. A. Fisher David Foster Joseph Fourier George Fox Philipp Frank Steven Frautschi Edward Fredkin Augustin-Jean Fresnel Karl Friston Benjamin Gal-Or Howard Gardner Lila Gatlin Michael Gazzaniga Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen GianCarlo Ghirardi J. Willard Gibbs James J. Gibson Nicolas Gisin Paul Glimcher Thomas Gold A. O. Gomes Brian Goodwin Julian Gough Joshua Greene Dirk ter Haar Jacques Hadamard Mark Hadley Ernst Haeckel Patrick Haggard J. B. S. Haldane Stuart Hameroff Augustin Hamon Sam Harris Ralph Hartley Hyman Hartman Jeff Hawkins John-Dylan Haynes Donald Hebb Martin Heisenberg Werner Heisenberg Hermann von Helmholtz Grete Hermann John Herschel Francis Heylighen Basil Hiley Art Hobson Jesper Hoffmeyer John Holland Don Howard John H. Jackson Ray Jackendoff Roman Jakobson E. T. Jaynes William Stanley Jevons Pascual Jordan Eric Kandel Ruth E. Kastner Stuart Kauffman Martin J. Klein William R. Klemm Christof Koch Simon Kochen Hans Kornhuber Stephen Kosslyn Daniel Koshland Ladislav Kovàč Leopold Kronecker Bernd-Olaf Küppers Rolf Landauer Alfred Landé Pierre-Simon Laplace Karl Lashley David Layzer Joseph LeDoux Gerald Lettvin Michael Levin Gilbert Lewis Benjamin Libet David Lindley Seth Lloyd Werner Loewenstein Hendrik Lorentz Josef Loschmidt Alfred Lotka Ernst Mach Donald MacKay Henry Margenau Lynn Margulis Owen Maroney David Marr Humberto Maturana James Clerk Maxwell John Maynard Smith Ernst Mayr John McCarthy Barbara McClintock Warren McCulloch N. David Mermin George Miller Stanley Miller Ulrich Mohrhoff Jacques Monod Vernon Mountcastle Gerd B. Müller Emmy Noether Denis Noble Donald Norman Travis Norsen Howard T. Odum Alexander Oparin Abraham Pais Howard Pattee Wolfgang Pauli Massimo Pauri Wilder Penfield Roger Penrose Massimo Pigliucci Steven Pinker Colin Pittendrigh Walter Pitts Max Planck Susan Pockett Henri Poincaré Michael Polanyi Daniel Pollen Ilya Prigogine Hans Primas Giulio Prisco Zenon Pylyshyn Henry Quastler Adolphe Quételet Pasco Rakic Nicolas Rashevsky Lord Rayleigh Frederick Reif Jürgen Renn Giacomo Rizzolati A.A. Roback Emil Roduner Juan Roederer Robert Rosen Frank Rosenblatt Jerome Rothstein David Ruelle David Rumelhart Michael Ruse Stanley Salthe Robert Sapolsky Tilman Sauer Ferdinand de Saussure Jürgen Schmidhuber Erwin Schrödinger Aaron Schurger Sebastian Seung Thomas Sebeok Franco Selleri Claude Shannon James A. Shapiro Charles Sherrington Abner Shimony Herbert Simon Dean Keith Simonton Edmund Sinnott B. F. Skinner Lee Smolin Ray Solomonoff Herbert Spencer Roger Sperry John Stachel Kenneth Stanley Henry Stapp Ian Stewart Tom Stonier Antoine Suarez Leonard Susskind Leo Szilard Max Tegmark Teilhard de Chardin Libb Thims William Thomson (Kelvin) Richard Tolman Giulio Tononi Peter Tse Alan Turing Robert Ulanowicz C. S. Unnikrishnan Nico van Kampen Francisco Varela Vlatko Vedral Vladimir Vernadsky Clément Vidal Mikhail Volkenstein Heinz von Foerster Richard von Mises John von Neumann Jakob von Uexküll C. H. Waddington Sara Imari Walker James D. Watson John B. Watson Daniel Wegner Steven Weinberg August Weismann Paul A. Weiss Herman Weyl John Wheeler Jeffrey Wicken Wilhelm Wien Norbert Wiener Eugene Wigner E. O. Wiley E. O. Wilson Günther Witzany Carl Woese Stephen Wolfram H. Dieter Zeh Semir Zeki Ernst Zermelo Wojciech Zurek Konrad Zuse Fritz Zwicky Presentations ABCD Harvard (ppt) Biosemiotics Free Will Mental Causation James Symposium CCS25 Talk Evo Devo September 12 Evo Devo October 2 Evo Devo Goodness Evo Devo Davies Nov12 |

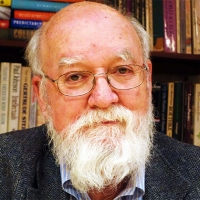

Daniel Dennett

Free Will an Illusion?

Free Will an Illusion?

Two Reasons for FreeWill FreeWill Worth Wanting Free Will IS Moral Competence

While he himself is a confirmed compatibilist, even a determinist, in "On Giving Libertarians What They Say They Want," Chapter 15 of his 1978 book Brainstorms, Daniel Dennett articulated the case for a two-stage model of free will better than any libertarian.

His "Valerian" model of decision making, named after the poet Paul Valéry, combines indeterminism to generate alternative possibilities, with (in our view, adequate) determinism to choose among the possibilities.

"The model of decision making I am proposing, has the following feature: when we are faced with an important decision, a consideration-generator whose output is to some degree undetermined produces a series of considerations, some of which may of course be immediately rejected as irrelevant by the agent (consciously or unconsciously). Those considerations that are selected by the agent as having a more than negligible bearing on the decision then figure in a reasoning process, and if the agent is in the main reasonable, those considerations ultimately serve as predictors and explicators of the agent's final decision." (Brainstorms, p.295)

Dennett gives six excellent reasons why this is the kind of free will that libertarians say they want. He says,

At times, Dennett seems pleased with his result.

"This result is not just what the libertarian is looking for, but it is a useful result nevertheless. It shows that we can indeed install indeterminism in the internal causal chains affecting human behavior at the macroscopic level while preserving the intelligibility of practical deliberation that the libertarian requires. We may have good reasons from other quarters for embracing determinism, but we need not fear that macroscopic indeterminism in human behavior would of necessity rob our lives of intelligibility by producing chaos." (p.292) "we need not fear that causal indeterminism would make our lives unintelligible." (p.298) "Even if one embraces the sort of view I have outlined, the deterministic view of the unbranching and inexorable history of the universe can inspire terror or despair, and perhaps the libertarian is right that there is no way to allay these feelings short of a brute denial of determinism. Perhaps such a denial, and only such a denial, would permit us to make sense of the notion that our actual lives are created by us over time out of possibilities that exist in virtue of our earlier decisions; that we trace a path through a branching maze that both defines who we are, and why, to some extent (if we are fortunate enough to maintain against all vicissitudes the integrity of our deliberational machinery) we are responsible for being who we are." (p.299)

At other times, he is skeptical.

His model, he says, "installs indeterminism in the right place for the libertarian, if there is a right place at all." and "it seems that all we have done is install indeterminism in a harmless place by installing it in an irrelevant place." (p.295)

Dennett seems to be soliciting interest in the model - from libertarian quarters? It is unfortunate that libertarians did not accept and improve Dennett's two-stage model. See What if Libertarians Had Accepted What Dan Dennett Gave Them in 1978?

If they had, the history of the free will problem would have been markedly different for the last forty years, perhaps successfully reconciling indeterminism with free will, as the best two-stage models now do, just as Hume reconciled freedom with determinism.

"There may not be compelling grounds from this quarter for favoring an indeterministic vision of the springs of our action, but if considerations from other quarters favor indeterminism, we can at least be fairly sanguine about the prospects of incorporating indeterminism into our picture of deliberation, even if we cannot yet see what point such an incorporation would have." (p.299)The point of incorporating indeterminism is, of course, to break the causal chain of pre-determinism, and to provide a source for novel ideas that were not already implicit in past events, thus explaining not only free will but creativity. This requires irreducible and ontological quantum indeterminacy. But Dennett does not think that irreducible quantum randomness provides anything essential beyond the deterministic pseudo-random number generation of computer science. "Isn't it the case that the new improved proposed model for human deliberation can do as well with a random-but-deterministic generation process as with a causally undetermined process? Suppose that to the extent that the considerations that occur to me are unpredictable, they are unpredictable simply because they are fortuitously determined by some arbitrary and irrelevant factors, such as the location of the planets or what I had for breakfast." (p.298)With his strong background in computer science and artificial intelligence, it is no surprise that Dennett continues to seek a "computational" model of the mind. But man is not a machine and the mind is not a computer.

Dennett on Free Will Worth Wanting

Dennett accepts the results of modern physics and does not deny the existence of quantum randomness. He calls himself a "naturalist" who wants to reconcile free will with natural science.

But what is "natural" about a computer-generated pseudo-random number sequence? The algorithm that generates it is quintessentially artificial. In the course of evolution, quantum mechanical randomness (along with the incredible quantum stability of information structures, without which no structures at all would exist) is naturally available to generate alternative possibilities.

Why would evolution need to create an algorithmic computational capability to generate those possibilities, when genuine and irreducible quantum randomness already provides them?

And who, before human computer designers, would be the author or artificer of the algorithm? Gregory Chaitin tells us that the information in a random-number sequence is only as much as is in the algorithm that created the sequence. And note that the artificial algorithm author implicitly has the kind of knowledge attributed to Laplace's Demon.

Since Dennett is a confirmed atheist, it seems odd that he has the "antipathy to chance" described by William James that is characteristic of religious believers. Quantum randomness is far more atheistic than pseudo-randomness, with the latter's implicit author or artificer.

Despite his qualms, Dennett seems to have located randomness in exactly the right place, the random generation of alternative considerations for his adequately determined selection process. In this first stage of free will, genuine quantum randomness (though not pseudo-randomness) breaks the causal chain of Laplacian determinism, without making the decisions themselves random.

In his Brainstorms 40th Edition, Dennett finally accepted his (and my) two-stage model!

In his introduction to the 40th edition of Brainstorms, Dennett writes (most generously)...

Chapter 15, "On Giving Libertarians What They Want," contains a model of free will that I viewed as an instructive throwaway when I concocted it, but it has recently found champions who credit me with finding the only defensible path (the "Valerian model") to a libertarian position on free will! I have conceded this much to Bob Doyle (the "Information Philosopher"—see http://www.informationphilosopher.com): Thanks to his relentless questioning I can now conceive of a situation in which I, compatibilist that I am, would ardently wish for the truth of genuine indeterminism so that I could act with absolute freedom: if I were playing rock-paper-scissors with God for high stakes! An omniscient and antagonistic (I'm an atheist after all) God could foil me in this competition unless my choice was quantum indeterministic, not merely chaotic and practically unpredictable. Some version of the Valerian model—minus the [in?]determinism—is all we need for free will worth wanting in this Godless world.And in perhaps Dennett's last video interview before his death, he concedes that my idea of quantum indeterminism in the first stage is needed (and criticizes Robert Sapolsky's new book Determined. See Daniel Dennett: Consciousness, AI, Free Will, Evolution, & Religion

Dennett on Austin's Putt

In his 2003 book, Freedom Evolves, Daniel Dennett says that Austin's Putt clarifies the mistaken fear that determinism reduces possibilities. Considering that Dennett is an actualist, who believes there is only one possible future, this bears close examination.

First, don't miss the irony that Dennett is using "possible worlds" thinking, which makes the one world we are in only able to have one possible future, our actual world.

Dennett says

Now that we have a clearer understanding of possible worlds, we can expose three major confusions about possibility and causation that have bedeviled the quest for an account of free will. First is the fear that determinism reduces our possibilities. We can see why the claim seems to have merit by considering a famous example proposed many years ago by John Austin:Consider the case where I miss a very short putt and kick myself because I could have holed it. It is not that I should have holed it if I had tried: I did try, and missed. It is not that I should have holed it if conditions had been different: that might of course be so, but I am talking about conditions as they precisely were, and asserting that I could have holed it. There is the rub. Nor does "I can hole it this time" mean that I shall hole it this time if I try or if anything else; for I may try and miss, and yet not be convinced that I could not have done it; indeed, further experiments may confirm my belief that I could have done it that time, although I did not. (Austin 1961, p. 166)Austin didn't hole the putt. Could he have, if determinism is true? The possible-worlds interpretation exposes the misstep in Austin's thinking. First, suppose that determinism holds, and that Austin misses, and let H be the sentence "Austin holes the putt." We now need to choose the set X of relevant possible worlds that we need to canvass to see whether he could have made it. Suppose X is chosen to be the set of physically possible worlds that are identical to the actual world at some time t0 prior to the putt. Since determinism says that there is at any instant exactly one physically possible future, this set of worlds has just one member, the actual world, the world in which Austin misses. So, choosing set X in this way, we get the result that H does not hold for any world in X. So it was not possible, on this reading, for Austin to hole the putt.

Evolution as an Algorithmic Process

Dennett maintains that biological evolution does not need quantum randomness, and says he was shocked by Jacques Monod's claim that random quantum processes are "essential" to evolution. Monod defines the importance of chance, or what he calls "absolute coincidence" as something like the intersection of causal chains that Aristotle calls an "accident." But, says Dennett, in his 1984 book Elbow Room,

when Monod comes to define the conditions under which such coincidences can occur, he apparently falls into the actualist trap. Accidents must happen if evolution is to take place, Monod says, and accidents can happen — "Unless of course we go back to Laplace's world, from which chance is excluded by definition and where Dr. Brown has been fated to die under Jones' hammer ever since the beginning of time." (Chance and Necessity, p. 115) If "Laplace's world" means just a deterministic world, then Monod is wrong. Natural selection does not need "absolute" coincidence. It does not need "essential" randomness or perfect independence; it needs practical independence — of the sort exhibited by Brown and Jones, and Jules and Jim, each on his own trajectory but "just happening" to intersect, like the cards being deterministically shuffled in a deck and just happening to fall into sequence. Would evolution occur in a deterministic world, a Laplacean world where mutation was caused by a nonrandom process? Yes, for what evolution requires is an unpatterned generator of raw material, not an uncaused generator of raw material. Quantum-level effects may indeed play a role in the generation of mutations, but such a role is not required by theory. It is not clear that "genuine" or "objective" randomness of either the quantum-mechanical sort or of the mathematical, informationally incompressible sort is ever required by a process, or detectable by a process. (Chaitin (1976) presents a Gödelian proof that there is no decision procedure for determining whether a series is mathematically random.) Even in mathematics, where the concept of objective randomness can find critical application within proofs, there are cases of what might be called practical indistinguishability.

Dennett's Challenge - Where Indeterminism Might Matter

Dennett has asked for cases where quantum indeterminism would make a substantive improvement over the pseudo-randomness that he thinks is enough for both biological evolution and free will. Dennett does not deny quantum indeterminacy. He just doubts that quantum randomness is necessary for free will. Information philosophy suggests that its great importance is that it breaks the causal chain of pre-determinism.

See the page Where, and When, is Randomness Located? for more details on where indeterminism is located, and for the positions of Bob Doyle, Bob Kane, and Al Mele compared to Dennett's Valerian Model of free will.

Quantum randomness has been available to evolving species for billions of years before pseudo-randomness emerges with humans. But Dennett does not think, as does Jacques Monod, for example, that quantum indeterminacy is necessary for biological evolution. The evolved virtual creatures of artificial life programs demonstrate for Dennett that biological evolution is an algorithmic process.

Here are five cases where quantum chance is critically important and better than pseudo-randomness. They all share a basic insight from information physics. Whenever a stable new information structure is created, two things must happen. The first is a collapse of the quantum wave function that allows one or more particles to combine in the new structure. The second is the transfer away from the structure to the cosmic background of the entropy required by the second law of thermodynamics to balance the local increase in negative entropy (information).

Laplace's Demon

Indeterministic events are unpredictable. Consequently, if any such probabilistic events occur, as Dennett admits, Laplace’s demon cannot predict the future. Information cosmology provides a second reason why such a demon is impossible. There was little or no information at the start of the universe. There is a great deal today, and more being created every day. There is not enough information in the past to determine the present, let alone completely determine the future. Creating future information requires quantum events, which are inherently indeterministic. The future is only probable, though it may be "adequately determined." Since there is not enough information available at any moment to comprehend all the information that will exist in the future, Laplace demons are impossible.

Intelligent Designers

Suppose that determinism is true, and that the chance driving spontaneous variation of the gene pool is merely epistemic (human ignorance), so that a deterministic algorithmic process is driving evolution. Gregory Chaitin has shown that the amount of information (and thus the true randomness) in a sequence of random numbers is no more than that in the algorithm that generates them.

This makes the process more comprehensible for a supernatural intelligent designer. And it makes the idea of an intelligent designer, deterministically controlling evolution with complete foreknowledge, more plausible. This is unfortunate.

An intelligent designer with a big enough computer could reverse engineer and alter the algorithm behind the pseudo-randomness driving evolution. This is just what genetic engineers do.

But cosmic rays, which are inherently indeterministic quantum events, damage the DNA to produce genetic mutations, variations in the gene pool. No intelligent designer could control such evolution.

So genetic engineers are intelligent designers, but they cannot control the whole of evolution.

Frankfurt Controllers

For almost fifty years, compatibilists have used Frankfurt-style Cases to show that alternative possibilities are not required for freedom of action and moral responsibility.

Bob Kane showed in 1985 that, if a choice is undetermined, the Frankfurt controller cannot tell until the choice is made whether the agent will do A or do otherwise. Compatibilists were begging the question by assuming a deterministic connection between a “prior sign” of a decision and the decision itself.

More fundamentally, information philosophy tells us that because chance (quantum randomness) helps generate the alternate possibilities, information about the choice does not come into the universe until the choice has been made.

Either way, the controller would have to intervene before the choice, in which case it is the controller that is responsible for the decision. Frankfurt controllers do not exist.

Dennett's Eavesdropper

We can call this Dennett's Eavesdropper because, in a discussion of quantum cryptography, Dennett agrees there is a strong reason to prefer quantum randomness to pseudo-randomness for encrypting secure messages. He sees that if a pseudo-random number sequence were used, a clever eavesdropper might discover the algorithm behind it and thus be able to decode the message.

Quantum cryptography and quantum computing use the non-local properties of entangled quantum particles. Non-locality shows up when the wave-function of a two-particle system collapses and new information comes into the universe. See the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen experiment.

Creating New Memes

Richard Dawkin’s unit of cultural information has the same limits as purely physical information. Claude Shannon’s mathematical theory of the communication of information says that information is not new without probabilistic surprises. Quantum physics is the ultimate source of that probability and the possibilities that surprise us. If the result were not truly unpredictable, it would be implicitly present in the information we already have. A new meme, like Dennett’s intuition pumps, skyhooks, and cranes, would have been already predictable there in the past and not his very original creations.

See the Information Philosopher contributions to Dennett's Fall 2010 seminar on Free Will at Tufts University.

References

Where Am I?

APA Presidential Address

For Teachers

For Scholars

On Giving Libertarians What They Say They Want

Chapter 15 of Brainstorms, 1978.

Why is the free will problem so persistent? Partly, I suspect, because it is called the free will problem. Hilliard, the great card magician, used to fool even his professional colleagues with a trick he called the tuned deck. Twenty times in a row he'd confound the quidnuncs, as he put it, with the same trick, a bit of prestidigitation that resisted all the diagnostic hypotheses of his fellow magicians. The trick, as he eventually revealed, was a masterpiece of subtle misdirection; it consisted entirely of the name, "the tuned deck", plus a peculiar but obviously non-functional bit of ritual. It was, you see, many tricks, however many different but familiar tricks Hilliard had to perform in order to stay one jump ahead of the solvers. As soon as their experiments and subtle arguments had conclusively eliminated one way of doing the trick, that was the way he would do the trick on future trials. This would have been obvious to his sophisticated onlookers had they not been so intent on finding the solution to the trick.

The so called free will problem is in fact many not very closely related problems tied together by a name and lots of attendant anxiety. Most people can be brought by reflection to care very much what the truth is on these matters, for each problem poses a threat: to our self-esteem, to our conviction that we are not living deluded lives, to our conviction that we may justifiably trust our grasp of such utterly familiar notions as possibility, opportunity and ability.*

There is no very good reason to suppose that an acceptable solution to one of the problems will be, or even point to, an acceptable solution to the others, and we may be misled by residual unallayed worries into rejecting or undervaluing partial solutions, in the misguided hope that we might allay all the doubts with one overarching doctrine or theory. But we don't have any good theories. Since the case for determinism is persuasive and since we all want to believe we have free will, compatibilism is the strategic favorite, but we must admit that no compatibilism free of problems while full of the traditional flavors of responsibility has yet been devised. The alternatives to compatibilism are anything but popular. Both the libertarian and the hard determinist believe that free will and determinism are incompatible. The hard determinist says: "So much of the worse for free will." The libertarian says: "So much the worse for determinism," at least with regard to human action. Both alternatives have been roundly and routinely dismissed as at best obscure, at worst incoherent. But alas for the compatibilist, neither view will oblige us by fading away. Their persistence, like Hilliard's success, probably has many explanations. I hope to diagnose just one of them. In a recent paper, David Wiggins has urged us to look with more sympathy at the program of libertarianism.' Wiggins first points out that a familiar argument often presumed to demolish libertarianism begs the question. The first premise of this argument is that every event is either causally determined or random. Then since the libertarian insists that human actions cannot be both free and determined, the libertarian must be supposing that any and all free actions are random. But one would hardly hold oneself responsible for an action that merely happened at random, so libertarianism, far from securing a necessary condition for responsible action, has unwittingly secured a condition that would defeat responsibility altogether. Wiggins points out that the first premise, that every event is either causally determined or random, is not the innocent logical truth it appears to be. The innocent logical truth is that every event is either causally determined or not causally determined. There may be an established sense of the word "random" that is unproblematically synonymous with "not causally determined", but the word "random" in common parlance has further connotations of pointlessness or arbitrariness, and it is these very connotations that ground our acquiescence in the further premise that one would not hold oneself responsible for one's random actions. It may be the case that whatever is random in the sense of being causally undetermined, is random in the sense connoting utter meaninglessness, but that is just what the libertarian wishes to deny. This standard objection to libertarianism, then, assumes what it must prove; it fails to show that undetermined action would be random action and hence action for which we could not be held responsible. But is there in fact any reasonable hope that the libertarian can find some defensible ground between the absurdity of "blind chance" on the one hand and on the other what Wiggins calls the cosmic unfairness of the determinist's view of these matters? Wiggins thinks there is. He draws our attention to a speculation of Russell's: "It might be that without infringing the laws of physics, intelligence could make improbable things happen, as Maxwell's demon would have defeated the second law of thermo-dynamics by opening the trap door to fast-moving particles and closing it to slow-moving particles. Wiggins sees many problems with the speculation, but he does, nevertheless, draw a glimmer of an idea from it. For indeterminism maybe all we really need to imagine or conceive is a world in which (a) there is some macroscopic indeterminacy founded in microscopic indeterminacy, and (b) an appreciable number of the free actions or policies or deliberations of individual agents, although they are not even in principle hypothetico-deductively derivable from antecedent conditions, can be such as to persuade us to fit them into meaningful sequences. We need not trace free actions back to volitions construed as little pushes aimed from outside the physical world. What we must find instead are patterns which are coherent and intelligible in the low level terms of practical deliberation, even though they are not amenable to the kind of generalization or necessity which is the stuff of rigorous theory. (p. 52)The "low level terms of practical deliberation" are, I take it, the familiar terms of intentional or reason-giving explanation. We typically render actions intelligible by citing their reasons, the beliefs and desires of the agent that render the actions at least marginally reasonable under the circumstances. Wiggins is suggesting then that if we could somehow make sense of human actions at the level of intentional explanation, then in spite of, the fact that those actions might be physically undetermined, they would not be random. Wiggins invites us to take this possibility seriously, but he has little further to say in elaboration or defense of this. He has said enough, however, to suggest to me a number of ways in which we could give libertarians what they seem to want. Wiggins asks only that human actions be seen to be intelligible in the low-level terms of practical deliberation. Surely if human actions were predictable in the low-level terms of practical deliberation, they would be intelligible in those terms. So I propose first to demonstrate that there is a way in which human behavior could be strictly undetermined from the physicist's point of view while at the same time accurately predictable from the intentional level. This demonstration, alas, will be very disappointing, for it relies on a cheap trick and what it establishes can be immediately seen to be quite extraneous to the libertarian's interests. But it is a necessary preamble to what I hope will be a more welcome contribution to the libertarian's cause. So let us get the disappointing preamble behind us. Here is how a bit of human behavior could be undetermined from the physicist's point of view, but quite clearly predictable by the intentionalist. Suppose we were to build an electronic gadget that I will call an answer box. The answer box is designed to record a person's answers to simple questions. It has two buttons, a Yes button, and a No button, and two foot pedals, a Yes pedal, and a No pedal, all clearly marked. It also has a little display screen divided in half, and on one side it says "use the buttons" and on the other side it says "use the pedals". We design this bit of apparatus so that only one half of this display screen is illuminated at any one time. Once a minute, a radium randomizer determines, in an entirely undetermined way of course, whether the display screen says "use the buttons" or "use the pedals". I now propose the following experiment. First, we draw up a list of ten very simple questions that have Yes or No answers, questions of the order of difficulty of "Do fish swim?" and "Is Texas bigger than Rhode Island?" We seat a subject at the answer box and announce that a handsome reward will be given to those who correctly follow all the experimental instructions, and a bonus will be given to those who answer all our questions correctly. Now, can the physicist in principle predict the subject's behavior? Let us suppose the subject is in fact a physically deterministic system, and let us suppose further that the physicist has perfect knowledge of the subject's initial state, all the relevant deterministic laws, and all the interactions within the closed situation of the experimental situation. Still, the unpredictable behavior of the answer box will infect the subject on a macroscopic scale with its own indeterminacy on at least ten occasions during the period the physicist must predict. So the best the physicist can do is issue a multiple disjunctive or multiple conditional prediction. Can the intentionalist do any better? Yes, of course. The intentionalist, having read the instructions given to the subject and having sized up the subject as a person of roughly normal intelligence and motivation, and having seen that all the odd numbered questions have Yes answers and the even numbered questions have No answers, confidently predicts that the subject will behave as follows: "The subject will give Yes answers to questions 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9, and the subject will answer the rest of the questions in the negative". There are no if's, or's or maybe's in those predictions. They are categorical and precise — precise enough for instance to appear in a binding contract or satisfy a court of law. This is, of course, the cheap trick I warned you about. There is no real difference in the predictive power of the two predictors. The intentionalist for instance is no more in a position to predict whether the subject will move finger or foot than the physicist is, and the physicist may well be able to give predictions that are tantamount to the intentionalist's. The physicist may for instance be able to make this prediction: "When question 6 is presented, if the illuminated sign on the box reads use the pedals, the subject's right foot will move at velocity k until it depresses the No pedal n inches, and if the illuminated sign says use the buttons, the subject's right index finger will trace a trajectory terminating on the No button." Such a prediction is if anything more detailed than the intentionalist's simple prediction of the negative answer to question 6, and it might in fact be more reliable and better grounded as well. But so what? What we are normally interested in, what we are normally interested in predicting, moreover, is not the skeletal motion of human beings but their actions, and the intentionalist can predict the actions of the subject (at least insofar as most of us would take any interest in them) without the elaborate rigmarole and calculations of the physicist. The possibility of indeterminacy in the environment of the kind introduced here, and hence the possibility of indeterminacy in the subject's reaction to that environment, is something with regard to which the intentionalistic predictive power is quite neutral. Still, we could not expect the libertarian to be interested in this variety of undetermined human behavior, behavior that is undetermined simply because the behavior of the answer box, something entirely external to the agent, is undetermined. Suppose then we move something like the answer box inside the agent. It is a commonplace of action theory that virtually all human actions can be accomplished or realized in a wide variety of ways. There are, for instance, indefinitely many ways of insulting your neighbor, or even of asserting that snow is white. And we are often not much interested, nor should we be, in exactly which particular physical motion accomplishes the act we intend. So let us suppose that our nervous system is so constructed. and designed that whenever in the implementation of an intention, our control system is faced with two or more options with regard to which we are non-partisan, a purely undetermined tie-breaking "choice" is made. There you are at the supermarket, wanting a can of Campbell's Tomato Soup, and faced with an array of several hundred identical cans of Campbell's Tomato Soup, all roughly equidistant from your hands. What to do? Before you even waste time and energy pondering this trivial problem, let us suppose, a perfectly random factor determines which can your hand reaches out for. This is of course simply a variation on the ancient theme of Buridan's ass, that unfortunate beast who, finding himself hungry, thirsty and equidistant between food and water, perished for lack of the divine nudge that in a human being accomplishes a truly free choice. This has never been a promising vision of the free choice of responsible agents, if only because it seems to secure freedom for such a small and trivial class of our choices. What does it avail me if I am free to choose this can of soup, but not free to choose between buying and stealing it? But however unpromising the idea is as a centerpiece for an account of free will, we must not underestimate its possible scope of application. Such trivial choice points seldom obtrude in our conscious deliberation, no doubt, but they are quite possibly ubiquitous nonetheless at an unconscious level. Whenever we choose to perform an action of a certain sort, there are no doubt slight variations in timing, style and skeletal implementation of those actions that are within our power but beneath our concern. For all we know, which variation occurs is undetermined. That is, the implementation of any one of our intentional actions may encounter undetermined choice points in many places in the causal chain. The resulting behavior would not be distinguishable to our everyday eyes, or from the point of view of our everyday interests, from behavior that was rigidly determined. What we are mainly interested in, as I said before, are actions, not motions, and what we are normally interested in predicting are actions. It is worth noting that not only can we typically predict actions from the intentional stance without paying heed to possibly undetermined variations of implementation of these actions, but we can even put together chains of intentional predictions that are relatively immune to such variation. In the summer of 1974 many people were confidently predicting that Nixon would resign. As the day and hour approached, the prediction grew more certain and more specific as to time and place; Nixon would resign not just in the near future, but in the next hour, and in the White House and in the presence of television cameramen and so forth. Still, it was not plausible to claim to know just how he would resign, whether he would resign with grace, or dignity, or with an attack on his critics, whether he would enunciate clearly or mumble or tremble. These details were not readily predictable, but most of the further dependent predictions we were interested in making did not hinge on these subtle variations. However Nixon resigned, we could predict that Goldwater would publicly approve of it, Cronkite would report that Goldwater had so approved of it, Sevareid would comment on it, Rodino would terminate the proceedings of the Judiciary Committee, and Gerald Ford would be sworn in as Nixon's successor. Of course some predictions we might have made at the time would have hinged crucially on particular details of the precise manner of Nixon's resignation, and if these details happened to be undetermined both by Nixon's intentions and by any other feature of the moment, then some human actions of perhaps great importance would be infected by the indeterminacy of Nixon's manner at the moment just as our exemplary subject's behavior was infected by the indeterminacy of the answer box. That would not, however, make these actions any the less intelligible to us as actions. This result is not just what the libertarian is looking for, but it is a useful result nevertheless. It shows that we can indeed install indeterminism in the internal causal chains affecting human behavior at the macroscopic level while preserving the intelligibility of practical deliberation that the libertarian requires. We may have good reasons from other quarters for embracing determinism, but we need not fear that macroscopic indeterminism in human behavior would of necessity rob our lives of intelligibility by producing chaos. Thus, philosophers such as Ayer and Hobart, who argue that free will requires determinism, must be wrong. There are some ways our world could be macroscopically indeterministic, without that fact remotely threatening the coherence of the intentionalistic conceptual scheme of action description presupposed by claims of moral responsibility. Still, it seems that all we have done is install indeterminism in a harmless place by installing it in an irrelevant place. The libertarian would not be relieved to learn that although his decision to murder his neighbor was quite determined, the style and trajectory of the death blow was not. Clearly, what the libertarian has in mind is indeterminism at some earlier point, prior to the ultimate decision or formation of intention, and unless we can provide that, we will not aid the libertarian's cause. But perhaps we can provide that as well. Let us return then, to Russell's speculation that intelligence might make improbable things happen. Is there any way that something like this could be accomplished? The idea of intelligence exploiting randomness is not unfamiliar. The poet, Paul Valéry, nicely captures the basic idea: It takes two to invent anything. The one makes up combinations; the other one chooses, recognizes what he wishes and what is important to him in the mass of the things which the former has imparted to him. What we call genius is much less the work of the first one than the readiness of the second one to grasp the value of what has been laid before him and to choose it.*Here we have the suggestion of an intelligent selection from what may be a partially arbitrary or chaotic or random production, and what we need is the outline of a model for such a process in human decision-making. An interesting feature of most important human decision-making is that it is made under time pressure. Even if there are, on occasion, algorithmic decision procedures giving guaranteed optimal solutions to our problems, and even if these decision procedures are in principle available to us, we may not have time or energy to utilize them. We are rushed, but moreover, we are all more or less lazy, even about terribly critical decisions that will affect our lives — our own lives, to say nothing of the lives of others. We invariably settle for a heuristic decision procedure; we satisfice (The term is Herbert Simon's. See his The Sciences of the Artificial (1969) for a review of the concept.); we poke around hoping for inspiration; we do our best to think about the problem in a more or less directed way until we must finally stop mulling, summarize our results as best we can, and act. A realistic model of such decision-making just might have the following feature: When someone is faced with an important decision, something in him generates a variety of more or less relevant considerations bearing on the decision. Some of these considerations, we may suppose, are determined to be generated, but others may be non-deterministically generated. For instance, Jones, who is finishing her dissertation on Aristotle and the practical syllogism, must decide within a week whether to accept the assistant professorship at the University of Chicago, or the assistant professorship at Swarthmore. She considers the difference in salaries, the probable quality of the students, the quality of her colleagues, the teaching load, the location of the schools, and so forth. Let us suppose that considerations A, B, C, D, E, and F occur to her and that those are the only considerations that occur to her, and that on the basis of those, she decides to accept the job at Swarthmore. She does this knowing of course that she could devote more time and energy to this deliberation, could cast about for other relevant considerations, could perhaps dismiss some of A-F as being relatively unimportant and so forth, but being no more meticulous, no more obsessive, than the rest of us about such matters, she settles for the considerations that have occurred to her and makes her decision. Let us suppose though, that after sealing her fate with a phone call, consideration G occurs to her, and she says to herself: "If only G had occurred to me before, I would certainly have chosen the University of Chicago instead, but G didn't occur to me". Now it just might be the case that exactly which considerations occur to one in such circumstances is to some degree strictly undetermined. If that were the case, then even the intentionalist, knowing everything knowable about Jones' settled beliefs and preferences and desires, might nevertheless be unable to predict her decision except perhaps conditionally. The intentionalist might be able to argue as follows: "If considerations A-F occur to Jones, then she will go Swarthmore," and this would be a prediction that would be grounded on a rational argument based on considerations A-F according to which Swarthmore was the best place to go. The intentionalist might go on to add, however, that if consideration G also occurs to Jones (which is strictly unpredictable unless we interfere and draw Jones' attention to G), Jones will choose the University of Chicago instead. Notice that although we are supposing that the decision is in this way strictly unpredictable except conditionally by the intentionalist, whichever choice Jones makes is retrospectively intelligible. There will be a rationale for the decision in either case; in the former case a rational argument in favor of Swarthmore based on A-F, and in the latter case, a rational argument in favor of Chicago, based on A-G. (There may, of course be yet another rational argument based on A-H, or I, or J, in favor of Swarthmore, or in favor of going on welfare, or in favor of suicide.) Even if in principle we couldn't predict which of many rationales could ultimately be correctly cited in justification or retrospective explanation of the choice made by Jones, we could be confident that there would be some sincere, authentic, and not unintelligible rationale to discover. The model of decision making I am proposing, has the following feature: when we are faced with an important decision, a consideration-generator whose output is to some degree undetermined produces a series of considerations, some of which may of course be immediately rejected as irrelevant by the agent (consciously or unconsciously). Those considerations that are selected by the agent as having a more than negligible bearing on the decision then figure in a reasoning process, and if the agent is in the main reasonable, those considerations ultimately serve as predictors and explicators of the agent's final decision. What can be said in favor of such a model, bearing in mind that there are many possible substantive variations on the basic theme? First, I think it captures what Russell was looking for. The intelligent selection, rejection and weighting of the considerations that do occur to the subject is a matter of intelligence making the difference. Intelligence makes the difference here because an intelligent selection and assessment procedure determines which microscopic indeterminacies get amplified, as it were, into important macroscopic determiners of ultimate behavior. Second, I think it installs indeterminism in the right place for the libertarian, if there is a right place at all. The libertarian could not have wanted to place the indeterminism at the end of the agent's assessment and deliberation. It would be insane to hope that after all rational deliberation had terminated with an assessment of the best available course of action, indeterminism would then intervene to flip the coin before action. It is a familiar theme in discussions of free will that the important claim that one could have done otherwise under the circumstances is not plausibly construed as the claim that one could have done otherwise given exactly the set of convictions and desires that prevailed at the end of rational deliberation. So if there is to be a crucial undetermined nexus, it had better be prior to the final assessment of the considerations on the stage, which is right where we have located it. Third, I think that the model is recommended by considerations that have little or nothing to do with the free will problem. It may well turn out to be that from the point of view of biological engineering, it is just more efficient and in the end more rational that decision-making should occur in this way. Time rushes on, and people must act, and there may not be time for a person to canvass all his beliefs, conduct all the investigations and experiments that he would see were relevant, assess every preference in his stock before acting, and it may be that the best way to prevent the inertia of Hamlet from overtaking us is for our decision-making processes to be expedited by a process of partially random generation and test. Even in the rare circumstances where we know there is, say, a decision procedure for determining the optimal solution to a decision problem, it is often more reasonable to proceed swiftly and by heuristic methods, and this strategic principle may in fact be incorporated as a design principle at a fairly fundamental level of cognitive-conative organization. A fourth observation in favor of the model is that it permits moral education to make a difference, without making all of the difference. A familiar argument against the libertarian is that if our moral decisions were not in fact determined by our moral upbringing, or our moral education, there would be no point in providing such an education for the young. The libertarian who adopted our model could answer that a moral education, while not completely determining the generation of considerations and moral decision-making, can nevertheless have a prior selective effect on the sorts of considerations that will occur. A moral education, like mutual discussion and persuasion generally, could adjust the boundaries and probabilities of the generator without rendering it deterministic. Fifth - and I think this is perhaps the most important thing to be said in favor of this model — it provides some account of our important intuition that we are the authors of our moral decisions. The unreflective compatibilist is apt to view decision-making on the model of a simple balance or scale on which the pros and cons of action are piled. What gets put on the scale is determined by one's nature and one's nurture, and once all the weights are placed, gravity as it were determines which way the scale will tip, and hence determines which way we will act. On such a view, the agent does not seem in any sense to be the author of the decisions, but at best merely the locus at which the environmental and genetic factors bearing on him interact to produce a decision. It all looks terribly mechanical and inevitable, and seems to leave no room for creativity or genius. The model proposed, however, holds out the promise of a distinction between authorship and mere implication in a causal chain. Consider in this light the difference between completing a lengthy exercise in long division and constructing a proof in, say, Euclidian geometry. There is a sense in which I can be the author of a particular bit of long division, and can take credit if it turns out to be correct, and can take pride in it as well, but there is a stronger sense in which I can claim authorship of a proof in geometry, even if thousands of school children before me have produced the very same proof. There is a sense in which this is something original that I have created. To take pride in one's computational accuracy is one thing, and to take pride in one's inventiveness is another, and as Valery claimed, the essence of invention is the intelligent selection from among randomly generated candidates. I think that the sense in which we wish to claim authorship of our moral decisions, and hence claim responsibility for them requires that we view them as products of intelligent invention, and not merely the results of an assiduous application of formulae. I don't want to overstate this case; certainly many of the decisions we make are so obvious, so black and white, that no one would dream of claiming any special creativity in having made them and yet would still claim complete responsibility for the decisions thus rendered. But if we viewed all our decision-making on those lines, I think our sense of our dignity as moral agents would be considerably impoverished. Finally, the model I propose points to the multiplicity of decisions that encircle our moral decisions and suggests that in many cases our ultimate decision as to which way to act is less important phenomenologically as a contributor to our sense of free will than the prior decisions affecting our deliberation process itself: the decision, for instance, not to consider any further, to terminate deliberation; or the decision to ignore certain lines of inquiry. These prior and subsidiary decisions contribute, I think, to our sense of ourselves as responsible free agents, roughly in the following way: I am faced with an important decision to make, and after a certain amount of deliberation, I say to myself: "That's enough. I've considered this matter enough and now I'm going to act," in the full knowledge that I could have considered further, in the full knowledge that the eventualities may prove that I decided in error, but with the acceptance of responsibility in any case. I have recounted six recommendations for the suggestion that human decision-making involves a non-deterministic generate-and-test procedure. First, it captures whatever is compelling in Russell's hunch. Second, it installs determinism in the only plausible locus for libertarianism (something we have established by a process of elimination). Third, it makes sense from the point of view of strategies of biological engineering. Fourth, it provides a flexible justification of moral education. Fifth, it accounts at least in part for our sense of authorship of our decisions. Sixth, it acknowledges and explains the importance of decisions internal to the deliberation process. It is embarrassing to note, however, that the very feature of the model that inspired its promulgation is apparently either gratuitous or misdescribed or both, and that is the causal indeterminacy of the generator. We have been supposing, for the sake of the libertarian, that the process that generates considerations for our assessment generates them at least in part by a physically or causally undetermined or random process. But here we seem to be trading on yet another imprecision or ambiguity in the word "random". When a system designer or programmer relies on a "random" generation process, it is not a physically undetermined process that is required, but simply a patternless process. Computers are typically equipped with a random number generator, but the process that generates the sequence is a perfectly deterministic and determinate process. If it is a good random number generator (and designing one is extraordinarily difficult, it turns out) the sequence will be locally and globally patternless. There will be a complete absence of regularities on which to base predictions about unexamined portions of the sequence.

Dennett here completely misses the point of quantum uncertainty invalidating determinism

Isn't it the case that the new improved proposed model for human deliberation can do as well with a random-but-deterministic generation process as with a causally undetermined process? Suppose that to the extent that the considerations that occur to me are unpredictable, they are unpredictable simply because they are fortuitously determined by some arbitrary and irrelevant factors, such as the location of the planets or what I had for breakfast. It appears that this alternative supposition diminishes not one whit the plausibility or utility of the model that I have proposed. Have we in fact given the libertarians what they really want without giving them indeterminism? Perhaps. We have given the libertarians the materials out of which to construct an account of personal authorship of moral decisions, and this is something that the compatibilistic views have never handled well. But something else has emerged as well. Just as the presence or absence of macroscopic indeterminism in the implementation style of intentional actions turned out to be something essentially undetectable from the vantage point of our Lebenswelt, a feature with no significant repercussions in the "manifest image", to use Sellars' term, so the rival descriptions of the consideration generator, as random-but-causally-deterministic versus random-and-causally-indeterministic, will have no clearly testable and contrary implications at the level of micro-neurophysiology, even if we succeed beyond our most optimistic fantasies in mapping deliberation processes onto neural activity.

That fact does not refute libertarianism, or even discredit the motivation behind it, for what it shows once again is that we need not fear that causal indeterminism would make our lives unintelligible. There may not be compelling grounds from this quarter for favoring an indeterministic vision of the springs of our action, but if considerations from other quarters favor indeterminism, we can at least be fairly sanguine about the prospects of incorporating indeterminism into our picture of deliberation, even if we cannot yet see what point such an incorporation would have. Wiggins speaks of the cosmic unfairness of determinism, and I do not think the considerations raised here do much to allay our worries about that. Even if one embraces the sort of view I have outlined, the deterministic view of the unbranching and inexorable history of the universe can inspire terror or despair, and perhaps the libertarian is right that there is no way to allay these feelings short of a brute denial of determinism. Perhaps such a denial, and only such a denial, would permit us to make sense of the notion that our actual lives are created by us over time out of possibilities that exist in virtue of our earlier decisions; that we trace a path through a branching maze that both defines who we are, and why, to some extent (if we are fortunate enough to maintain against all vicissitudes the integrity of our deliberational machinery) we are responsible for being who we are. That prospect deserves an investigation of its own. All I hope to have shown here is that it is a prospect we can and should take seriously.

"Could Have Done Otherwise"

Chapter 6 of Elbow Room, 1984.

I. Do We Care Whether We Could Have Done Otherwise?

In the midst of all the discord and disagreement among philosophers about free will, there are a few calm islands of near unanimity. As van Inwagen notes: