Statistical Mechanics

Although twentieth-century quantum physics provides the strongest evidence for the existence of ontological chance and randomness in the universe, statistics and probability entered physics long before the famous "uncertainty" principle in quantum mechanics was proposed by Werner Heisenberg in 1927.

Every scientist who made major contributions to the probabilistic nature of the world had some doubts as to whether the use of probability implies that chance is real. Is the appearance of randomness a consequence of the limits on human knowledge and merely epistemological? Or is randomness a fundamental part of the external world and thus ontological?

Heisenberg himself often maintained that our understanding of reality is limited by what we can know about the microscopic world. But he also said quantum mechanics makes the world acausal. His choice of "uncertainty" was unfortunate. Is the world fundamentally indeterministic? Or is it only because we cannot discover - we are uncertain about - the underlying determinism that gives rise to the appearance of indeterminism? Like the mathematicians who invented the calculus of probabilities, the physicists who reduced thermodynamics to statistical mechanics were skeptical about ontological randomness.

In 1860, James Clerk Maxwell, the first physicist to use statistics and probability, discovered the distribution of velocities of atoms or molecules in a gas. Although there was no evidence for the existence of atoms until Albert Einstein's work on Brownian motion in 1905, Maxwell and Ludwig Boltzmann showed that the macroscopic laws of thermodynamics could be explained if gases consist of microscopic atoms in motion. They used the calculus of probabilities to reduce thermodynamics to statistical mechanics.

Paradoxically, ignorance of the details of processes at the atomic level is overcome by the power of averages over large numbers of cases. Mean values of any property get more and more accurate as the number of independent events gets large. The number of gas particles in a cubic centimeter of air is truly astronomical, close to the number of stars in the observable universe. For this reason, gas laws like PV = NRT derived from statistical mechanics appear to be adequately or statistically deterministic.

Discrete Particles

To refine a famous comment by Richard Feynman, if there is just one bit of information that could survive the destruction of knowledge, so as to give future scientists the fastest recovery of physics, it would be that the contents of the universe are made up of discrete particles. This is now the standard model of particle physics. It grew out of the study of ordinary gases.

Gas particles are distributed in ordinary coordinate space (x, y, z) and in a conjugate momentum (or energy) space (px, py, pz). These two spaces are combined to form a six-dimensional space called a "phase space," one element of which is Δx Δy Δz Δpx Δpy Δpz. Particles are found distributed in proportion to the volume of those spaces. But phase space elements are weighted by an exponential factor that reduces the probability of particles being found in higher energy spaces. The factor is e - p2/2mkT = e - E / kT, today known as the "Boltzmann factor," though it was first found by Maxwell.

E is the particle energy, p is the particle momentum ( = mv, mass times velocity), T is the absolute temperature (in degrees Kelvin), e is the base of natural logarithms, and k is Boltzmann's constant (so named by Max Planck). As E increases, the probability of finding particles with that energy decreases exponentially. But as the temperature T rises, the probability of finding particles with any given energy E increases.

With the hindsight of quantum physics, we can envision the distribution of particles as the integer number of particles (or "occupation number") that are in the smallest possible volumes of this 6-dimensional "phase space" allowed by quantum mechanics. These have the dimensions of h3, where h is Planck's constant. h has the dimensions of action (equal to momentum times position) and is called the quantum of action.

This minimum phase space volume of h3 is the result of Heisenberg's uncertainty principle for each dimension, Δp Δx = h. It is as if space itself is divided into these small "cells." But space is continuous, like time. Space and time are abstract tools for assigning numbers to particle properties like location and motion. The minimum volume h3 corresponds to locations and speeds where there is a non-zero probability of finding a discrete particle.

Although classical statistical mechanics did not include these quantum volumes, Boltzmann did divide phase space into discrete "coarse-grained" volumes for calculation purposes. The important new insight of classical statistical mechanics was accepting the radical idea of the ancient Greeks that matter comes in invisible discrete discontinuous lumps.

Maxwell not only accepted the idea of atoms and molecules, he deduced their distribution among different possible velocities,

N ( v ) dv = (4 / α2 √π) v2 e - v2 / α2 dv.

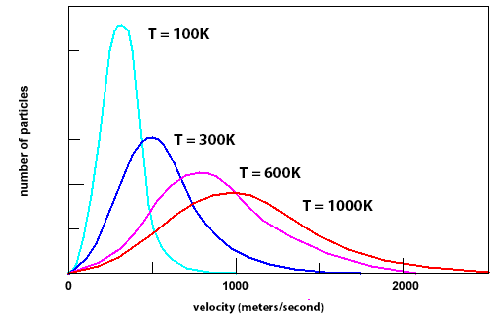

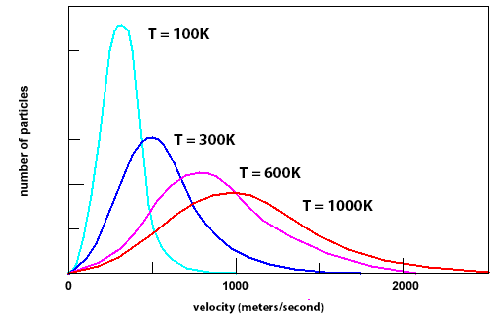

The figure shows the number of particles with a given velocity at different temperatures. When heat is added and the temperature rises, the average velocity gets higher and there are fewer particles with low velocities, since the total number of molecules is a constant.

Maxwell did not know about the future Boltzmann's constant and its temperature relationship, but he knew that the term α2 is a measure of the average velocity squared, and so of the energy ( mv2 / 2 ).

Maxwell did know the factor of √π from the normal distribution of independent random events.

Maxwell did not know about the future Boltzmann's constant and its temperature relationship, but he knew that the term α2 is a measure of the average velocity squared, and so of the energy ( mv2 / 2 ).

Maxwell did know the factor of √π from the normal distribution of independent random events.

The velocity distribution has two distinction regions which were critically important in Max Planck's attempt to discover the distribution of electromagnetic radiation. For very low energies, the number rises as the square of the velocity. It then turns around at a maximum near the average velocity, very like the errors curve. It then declines slowly like the long exponential tail of the normal distribution of errors because of the Boltzmann factor.

Ludwig Boltzmann explained that probabilities can give definite results because of the large number of particles in a gas, but that the use of probabilities does not imply any uncertainty.

The velocity distribution has two distinction regions which were critically important in Max Planck's attempt to discover the distribution of electromagnetic radiation. For very low energies, the number rises as the square of the velocity. It then turns around at a maximum near the average velocity, very like the errors curve. It then declines slowly like the long exponential tail of the normal distribution of errors because of the Boltzmann factor.

Ludwig Boltzmann explained that probabilities can give definite results because of the large number of particles in a gas, but that the use of probabilities does not imply any uncertainty.

The mechanical theory of heat assumes that the molecules of a gas are not at rest, but rather are in the liveliest motion. Hence, even though the body does not change its state, its individual molecules are always changing their states of motion, and the various molecules take up many different positions with respect to each other. The fact that we nevertheless observe completely definite laws of behaviour of warm bodies is to be attributed to the circumstance that the most random events, when they occur in the same proportions, give the same average value. For the molecules of the body are indeed so numerous, and their motion is so rapid, that we can perceive nothing more than average values.

One might compare the regularity of these average values with the amazing constancy of the average numbers provided by statistics, which are also derived from processes each of which is determined by a completely unpredictable interaction with many other factors. The molecules are likewise just so many individuals having the most varied states of motion, and it is only because the number of them that have, on the average, a particular state of motion is constant, that the properties of the gas remain unchanged.

The determination of average values is the task of probability theory. Hence, the problems of the mechanical theory of heat are also problems of probability theory.

In the 1870's, Boltzmann clearly sees probability as a deterministic theory.

It would, however, be erroneous to believe that the mechanical theory of heat is therefore afflicted with some uncertainty because the principles of probability theory are used. One must not confuse an incompletely known law, whose validity is therefore in doubt, with a completely known law of the calculus of probabilities; the latter, like the result of any other calculus, is a necessary consequence of definite premises, and is confirmed, insofar as these are correct, by experiment, provided sufficiently many observations have been made, which is always the case in the mechanical theory of heat because of the enormous number of molecules involved.

("Further Studies on the Thermal Equilibrium of Gas Molecules," Vienna Academy of Sciences, 1872)

|

|

This visualization of gas molecules in coordinate space shows that occasional high density fluctuations occur, but they are very quickly eliminated, as Boltzmann expected.

The darkest spots are condensations of particles, slight local reductions of the entropy. But they cannot be maintained. Although the microscopic motions are violent and random, as Boltzmann says, the overall average of motions is remarkably stable.

|

The Second Law of Thermodynamics

Beyond his ability to visualize the above "liveliest states of motion" for atoms, Boltzmann's greatest work was his attempt to prove the second law of thermodynamics. The second law says that isolated systems always approach thermal equilibrium. Boltzmann showed that if the velocities of gas molecules were initially not in the Maxwell distribution above, they would always approach that distribution, and do it rapidly at standard temperatures and pressures (as we all know from experience).

Boltzmann then developed a mathematical expression for entropy, the quantity in classical thermodynamics that is a maximum for systems in thermal equilibrium.

At first Boltzmann tried to do this with the dynamical theories of classical mechanics. The particles in his system would move around in phase space according to deterministic Newtonian laws. They collide with one another as hard spheres (elastic collisions). Only two-particle collisions were included, assuming three-particle collisions are rare. As it turns out, three-particle collisions would be essential for proving Boltzmann's insights.

But Boltzmann's mentor, Josef Loschmidt, criticized the results. Any dynamical system, he said, will evolve in reverse if all the particles could have their velocities reversed. Apart from the practical impossibility of doing this, Loschmidt had shown that systems could exist for which the entropy should decrease instead of increasing. This is called Loschmidt's Reversibility Objection, or the problem of microscopic reversibility.

Loschmidt's criticism forced Boltzmann to reformulate his proof of the second law with purely statistical considerations based on probability theory.

He looked at all the possible distributions for particles in phase space consistent with a given total energy. Since phase space is continuous, there is an infinity of positions for every particle. So Boltzmann started by limiting possible energy values to discrete amounts ε, 2ε, 3ε, etc. He thought he would eventually let ε go to zero, but his discrete "coarse-graining" gets him much closer to modern quantum physics. He replaced all his integrals by discrete sums (something the "founders of quantum mechanics" in the nineteen-twenties would do).

In 1948,

Claude Shannon found a similar expression to describe the amount of

information,

Σi pi log pi , thus connecting his information to Boltzmann's entropy.

Σ f(E) log f(E) .

Today scientists identity this quantity with the thermodynamic entropy S, defined as the change of heat Q added to a system divided by the temperature T,

dS = dQ/T

In terms of a sum over possible states, S is now written as the logarithm of the total number of possible states W multiplied by Boltzmann's constant,

S = k log W.

Boltzmann was discouraged to find that a group of scientists who still hoped to deny the existence of atoms continued to criticize his "H-Theorem." They included Henri Poincaré, an expert on the three-body problem, Max Planck, who himself hoped to prove the second law, and a young student of Planck's named Ernst Zermelo who was an extraordinary mathematician, later the founder of axiomatic set theory.

Poincaré's three-body problem suggested that, given enough time, a bounded world, governed only by the laws of mechanics, will always pass through a state very close to its initial state. Zermelo accepted Boltzmann's claim that a system will most likely be found in a macrostate with the largest number of microstates, but he argued that given enough time it would return to a less probable state. Boltzmann's H-Theorem of perpetual increase of entropy must therefore be incorrect.

Information physics has shown that, when quantum physics and the interaction of electromagnetic radiation with matter are taken into account, the Loschmidt objection and the Zermelo objection fail to prevent entropy from increasing in our open universe.

Unfortunately for Boltzmann, he died before the significance of radiation and the quantum were appreciated, and before Einstein proved the existence of his atoms. And ironically, it was Max Planck, who was Zermelo's mentor and one of those strongly opposing both Boltzmann's ideas of atoms and his use of statistics, who was to find the distribution law for electromagnetic radiation.

Adding to the injustice, Planck used Boltzmann's statistical ideas, his assumption about discrete energies, and his ideas about entropy to develop the Planck radiation law. The radiation distribution has almost exactly the same shape as the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution for particle velocities. You can see the initial rise as the square of the radiation frequency v, and after the maximum the decline according to the Boltzmann factor e - hv / kT, where the energy E = hv is Planck's new constant h times the radiation frequency. The reason for the similarity is profound - electromagnetic radiation - light- is also made of particles.

Nv dv = (2 v2 / c 2 e - hv / kT dv).

The figure shows the number of photons with a given wavelength at different temperatures. When heat is added and the temperature rises, the average photon energy (hv = hc/λ) gets higher at all wavelengths. The maximum number of photons moves to shorter wavelengths (higher energies). Unlike the Maxwell distribution, where the total number of molecules is a constant, additional heat shows up as more photons at all wavelengths. The number of photons is not conserved.

Compounding the irony and injustice for Boltzmann still further, Planck, long the opponent of his discrete particles and statistical mechanics, used Boltzmann's assumption that energies come in discrete amounts, hv, 2 hv, 3 hv, etc. He called them quanta of energy. Planck thereby launched the twentieth-century development of quantum mechanics, without really understanding the full implications of quantizing the energy. He thought quantization was just a mathematical trick to get the right formula.

Albert Einstein said that "the formal similarity between the curve of the chromatic distribution of thermal radiation and the Maxwellian distribution law of velocities is so striking that it could not have been hidden for long." But for over twenty years few others than Einstein saw so clearly that it implies that light itself is a quantized discrete particle! Planck refused to believe it for many years.

So did Niels Bohr, despite his famous 1913 work that quantized the energy levels for electrons in his Bohr model of the atom. Bohr postulated two things, 1) that the energy levels in the atom are discrete and 2) that when an electron jumps between levels it emits or absorbs energy E = hv, where the energy E is the difference between the two levels E = En - Em.

After independently developing the theory of statistical mechanics in 1902-1904, extending it well beyond Boltzmann, Einstein hypothesized in 1905 that light comes in bundles of localized energy that he called light quanta (now known as photons). Although it is hard to believe, Niels Bohr denied the existence of photons well into the nineteen-twenties, although today's textbooks teach that quantum jumps in the Bohr atom emit or absorb photons, in this case an injustice to Einstein. Bohr pictured the radiation in his discrete quantum jumps as a continuous wave. He was reluctant to depart from the Maxwell's classical laws of electromagnetism.

Einstein told friends that his hypothesis of light quanta was more revolutionary than his theory of special relativity published the same year. It was Einstein, not Planck or Bohr or Heisenberg, who should be recognized as the father of quantum theory. He first saw the mysterious aspects of quantum physics like wave-particle duality, nonlocality, and the ontological nature of chance, more deeply than any other physicist has ever seen them.

Einstein famously abhorred chance ("God does not play dice"), but he did not hesitate to tell other physicists that chance seems to be an unavoidable part of quantum theory.

Compounding the irony and injustice for Boltzmann still further, Planck, long the opponent of his discrete particles and statistical mechanics, used Boltzmann's assumption that energies come in discrete amounts, hv, 2 hv, 3 hv, etc. He called them quanta of energy. Planck thereby launched the twentieth-century development of quantum mechanics, without really understanding the full implications of quantizing the energy. He thought quantization was just a mathematical trick to get the right formula.

Albert Einstein said that "the formal similarity between the curve of the chromatic distribution of thermal radiation and the Maxwellian distribution law of velocities is so striking that it could not have been hidden for long." But for over twenty years few others than Einstein saw so clearly that it implies that light itself is a quantized discrete particle! Planck refused to believe it for many years.

So did Niels Bohr, despite his famous 1913 work that quantized the energy levels for electrons in his Bohr model of the atom. Bohr postulated two things, 1) that the energy levels in the atom are discrete and 2) that when an electron jumps between levels it emits or absorbs energy E = hv, where the energy E is the difference between the two levels E = En - Em.

After independently developing the theory of statistical mechanics in 1902-1904, extending it well beyond Boltzmann, Einstein hypothesized in 1905 that light comes in bundles of localized energy that he called light quanta (now known as photons). Although it is hard to believe, Niels Bohr denied the existence of photons well into the nineteen-twenties, although today's textbooks teach that quantum jumps in the Bohr atom emit or absorb photons, in this case an injustice to Einstein. Bohr pictured the radiation in his discrete quantum jumps as a continuous wave. He was reluctant to depart from the Maxwell's classical laws of electromagnetism.

Einstein told friends that his hypothesis of light quanta was more revolutionary than his theory of special relativity published the same year. It was Einstein, not Planck or Bohr or Heisenberg, who should be recognized as the father of quantum theory. He first saw the mysterious aspects of quantum physics like wave-particle duality, nonlocality, and the ontological nature of chance, more deeply than any other physicist has ever seen them.

Einstein famously abhorred chance ("God does not play dice"), but he did not hesitate to tell other physicists that chance seems to be an unavoidable part of quantum theory.

Maxwell did not know about the future Boltzmann's constant and its temperature relationship, but he knew that the term α2 is a measure of the average velocity squared, and so of the energy ( mv2 / 2 ).

Maxwell did know the factor of √π from the normal distribution of independent random events.

Maxwell did not know about the future Boltzmann's constant and its temperature relationship, but he knew that the term α2 is a measure of the average velocity squared, and so of the energy ( mv2 / 2 ).

Maxwell did know the factor of √π from the normal distribution of independent random events.

The velocity distribution has two distinction regions which were critically important in Max Planck's attempt to discover the distribution of electromagnetic radiation. For very low energies, the number rises as the square of the velocity. It then turns around at a maximum near the average velocity, very like the errors curve. It then declines slowly like the long exponential tail of the normal distribution of errors because of the Boltzmann factor.

Ludwig Boltzmann explained that probabilities can give definite results because of the large number of particles in a gas, but that the use of probabilities does not imply any uncertainty.

The velocity distribution has two distinction regions which were critically important in Max Planck's attempt to discover the distribution of electromagnetic radiation. For very low energies, the number rises as the square of the velocity. It then turns around at a maximum near the average velocity, very like the errors curve. It then declines slowly like the long exponential tail of the normal distribution of errors because of the Boltzmann factor.

Ludwig Boltzmann explained that probabilities can give definite results because of the large number of particles in a gas, but that the use of probabilities does not imply any uncertainty.

Compounding the irony and injustice for Boltzmann still further, Planck, long the opponent of his discrete particles and statistical mechanics, used Boltzmann's assumption that energies come in discrete amounts, hv, 2 hv, 3 hv, etc. He called them quanta of energy. Planck thereby launched the twentieth-century development of quantum mechanics, without really understanding the full implications of quantizing the energy. He thought quantization was just a mathematical trick to get the right formula.

Albert Einstein said that "the formal similarity between the curve of the chromatic distribution of thermal radiation and the Maxwellian distribution law of velocities is so striking that it could not have been hidden for long." But for over twenty years few others than Einstein saw so clearly that it implies that light itself is a quantized discrete particle! Planck refused to believe it for many years.

So did Niels Bohr, despite his famous 1913 work that quantized the energy levels for electrons in his Bohr model of the atom. Bohr postulated two things, 1) that the energy levels in the atom are discrete and 2) that when an electron jumps between levels it emits or absorbs energy E = hv, where the energy E is the difference between the two levels E = En - Em.

After independently developing the theory of statistical mechanics in 1902-1904, extending it well beyond Boltzmann, Einstein hypothesized in 1905 that light comes in bundles of localized energy that he called light quanta (now known as photons). Although it is hard to believe, Niels Bohr denied the existence of photons well into the nineteen-twenties, although today's textbooks teach that quantum jumps in the Bohr atom emit or absorb photons, in this case an injustice to Einstein. Bohr pictured the radiation in his discrete quantum jumps as a continuous wave. He was reluctant to depart from the Maxwell's classical laws of electromagnetism.

Einstein told friends that his hypothesis of light quanta was more revolutionary than his theory of special relativity published the same year. It was Einstein, not Planck or Bohr or Heisenberg, who should be recognized as the father of quantum theory. He first saw the mysterious aspects of quantum physics like wave-particle duality, nonlocality, and the ontological nature of chance, more deeply than any other physicist has ever seen them.

Einstein famously abhorred chance ("God does not play dice"), but he did not hesitate to tell other physicists that chance seems to be an unavoidable part of quantum theory.

Compounding the irony and injustice for Boltzmann still further, Planck, long the opponent of his discrete particles and statistical mechanics, used Boltzmann's assumption that energies come in discrete amounts, hv, 2 hv, 3 hv, etc. He called them quanta of energy. Planck thereby launched the twentieth-century development of quantum mechanics, without really understanding the full implications of quantizing the energy. He thought quantization was just a mathematical trick to get the right formula.

Albert Einstein said that "the formal similarity between the curve of the chromatic distribution of thermal radiation and the Maxwellian distribution law of velocities is so striking that it could not have been hidden for long." But for over twenty years few others than Einstein saw so clearly that it implies that light itself is a quantized discrete particle! Planck refused to believe it for many years.

So did Niels Bohr, despite his famous 1913 work that quantized the energy levels for electrons in his Bohr model of the atom. Bohr postulated two things, 1) that the energy levels in the atom are discrete and 2) that when an electron jumps between levels it emits or absorbs energy E = hv, where the energy E is the difference between the two levels E = En - Em.

After independently developing the theory of statistical mechanics in 1902-1904, extending it well beyond Boltzmann, Einstein hypothesized in 1905 that light comes in bundles of localized energy that he called light quanta (now known as photons). Although it is hard to believe, Niels Bohr denied the existence of photons well into the nineteen-twenties, although today's textbooks teach that quantum jumps in the Bohr atom emit or absorb photons, in this case an injustice to Einstein. Bohr pictured the radiation in his discrete quantum jumps as a continuous wave. He was reluctant to depart from the Maxwell's classical laws of electromagnetism.

Einstein told friends that his hypothesis of light quanta was more revolutionary than his theory of special relativity published the same year. It was Einstein, not Planck or Bohr or Heisenberg, who should be recognized as the father of quantum theory. He first saw the mysterious aspects of quantum physics like wave-particle duality, nonlocality, and the ontological nature of chance, more deeply than any other physicist has ever seen them.

Einstein famously abhorred chance ("God does not play dice"), but he did not hesitate to tell other physicists that chance seems to be an unavoidable part of quantum theory.